Eric Higgs, December 11th, 2023

At the Mountain Legacy Project we are raising an even louder cheer this year to mark the 2023 theme of International Mountain Day: restoring mountain ecosystems. The MLP traces its origin to ecosystem restoration, which continues to be the predominant challenge pushing our work forward.

In 1992 the late David Schindler and a team of University of Alberta researchers prepared to undertake a comprehensive investigation into the health of Jasper National Park, that large Canadian icon of wild places. For many, the landscapes of Jasper represented a timeless wilderness: slow changing and resilient. We saw it differently. The main valley bottom was streaked with roads and railways, pipelines and telecommunication cables. There were abandoned gravel pits, old and new campgrounds, and outlying commercial facilities. In high elevation lakes Schindler’s team detected long-range contaminants, and some of those lakes had been stocked decades earlier by non-native sport fish. Climate change was dawning as a major issue.

Alas, the comprehensive investigation didn’t lift off. Large-scale funding was denied, likely because it was difficult to convince grantors that Jasper was anything but a healthy place. We prevailed, but primarily through individual initiatives.

In 1995, the same year I was elected as Secretary of the Society for Ecological Restoration, a team of us launched the interdisciplinary “Culture, Ecology and Restoration” project. Animated by our earlier understandings of development and change in Jasper, we sought to assess what restoration would look like in a landscape so rooted in culturally contested ideas of unpeopled wilderness. The following year saw the publication of William Cronon’s now classic article, “The Trouble With Wilderness,” and a team of University of Alberta graduate students fanned out across Jasper to track historical change. In one of those fateful encounters, Jeanine Rhemtulla was pointed to the boxes of photograph albums that portrayed the landscape in 1915. Boxes that led eventually to glass plate negatives and the knowledge that most of western Canada’s mountains were mapped topographically using photography.

Jeanine Rhemtulla, Jasper National Park, Station: Chak Peak I, 1999

Our search for historical records was rooted in a shared recognition of the critical relationship between past, present and future in ecosystem restoration. The past—often prior to particular disturbances—provides references that inform restoration actions in the present and for the future. The photographs—systematic, comprehensive, and high resolution—offered something exceedingly rare for restoration activities: highly detailed accounts of pattern, structure, and composition of ecosystems from a century before. More than this they showed the legacies of Indigenous land management.

Our first repeat images were taken late in the summer of 1996, and in earnest in 1998-99, to repeat the entire 1915 work of Dominion Land Surveyor, Morrison Parsons Bridgland. We hiked, scrambled and flew to 92 locations taking 735 photographs from exactly the same location as the historic ones.

Eric Higgs and Jeanine Rhemtulla, Jasper National Park, Station: Fiddle II, 1999

For the last 25 years teams from the Mountain Legacy Project have visited more than a thousand locations and taken more than 10,000 repeat photographs. These are assembled in the largest publicly accessible image database of its kind in the world (explore.mountainlegacy.ca). We have partnered with Library and Archives Canada to bring historic photographic collections to light and with land-based partners such as Parks Canada and Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. Recently we have worked with Indigenous partners such as the Stoney Nakoda and Kainai Nations, to use the images in the service of reconciliation and resurgence.

Our attention throughout has been on restoring mountain ecosystems and especially in recognizing that the altitudinal gradients of mountains and our northerly latitude are producing rapid changes in snow- and ice-pack, forest composition, fire patterns, human activity, wildlife movements, invasive species, and more. The classical version of restoration (Restoration 1.0), in which history determines the future, has to be rewritten at least partly to comprehend the dynamics of unprecedented change. I teamed up with colleagues from around the world to develop models for restoration in a world of rapid change, including the concept of novel ecosystems. Restoration 2.0 will need to address rapid change while acknowledging critical historical trajectories and the unfolding of new patterns and processes. In other words, mountains of change.

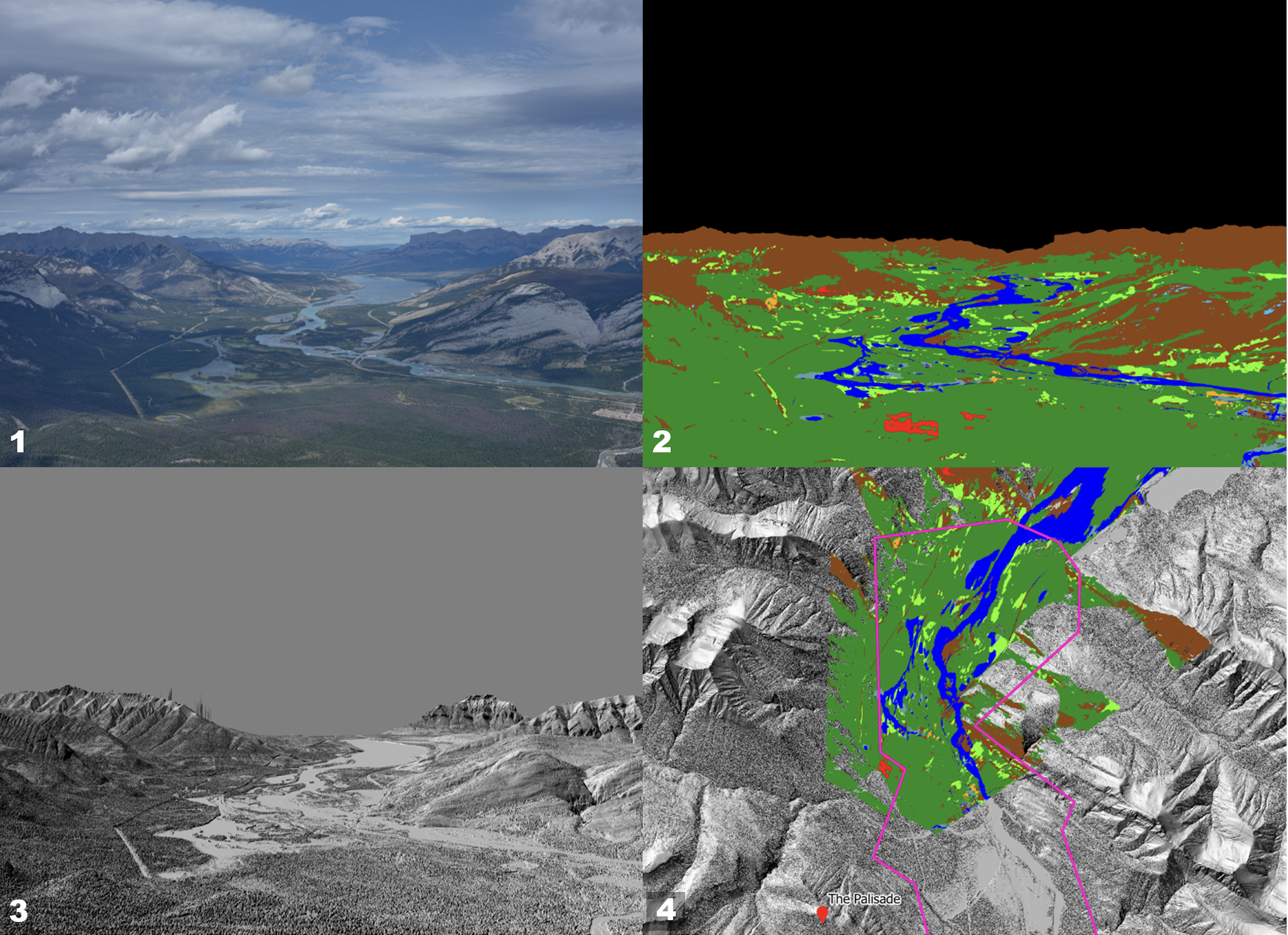

James Tricker, 2023. Example of workflow for georeferencing land cover data derived from an oblique photograph.

1. An oblique repeat photograph captured from The Palisades in Jasper National Park. 2. Land cover data automatically classified from the oblique image using a machine learning tool. 3. A virtual photograph, replicating the original photograph field of view, is generated using camera metadata and elevation data. The original photograph is then aligned to the virtual photograph using control points and a perspective transformation, which are then used to align the image classification to the virtual photograph. 4. The cell values from the aligned image classification are then georeferenced by exploiting the relationship between the virtual photograph and elevation data.

So, our work presses on, unlocking the Mountain Legacy Project images for broader application. It was gratifying to participate in the recently-published first ever Canadian Mountain Assessment (with some MLP images!). The Assessment had many firsts, including the diversity of contributing authors, interdisciplinary reach, and a bold commitment to diverse ways of knowing. MLP researchers are developing new software allows the automated classification of land cover in the images and geo-referencing of the ground-based photographs for analysis in Geographic Information Systems. Meanwhile, we are exploring how design disciplines such as architecture and landscape architecture can engage more directly with repeat photography and ecosystem restoration, and working with Indigenous partners to consider the significance of Indigenous stewardship in mountain regions. Altogether, our latest research opens significant potential for using the images in the service of diverse restoration and reconciliation goals.

Historic image from Fording River Pass West (B10) station, taken by D. B. Dowling in 1905

Further Reading

Cronon, W. 1996. The trouble with wilderness. Environmental History 1:7-28.

Higgs, E., D. A. Falk, A. Guerrini, M. Hall, J. Harris, R. J. Hobbs, S. T. Jackson, J. M. Rhemtulla, and W. Throop. 2014. The changing role of history in restoration ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12:499-506.

Higgs, E. 2003. Nature By Design: People, Natural Process and Ecological Restoration. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

MacLaren, I. S., (with E. Higgs, and G. Zezulka-Mailloux). 2005. Mapper of Mountains: M.P. Bridgland in the Canadian Rockies 1902-1930. University of Alberta Press, Edmonton.