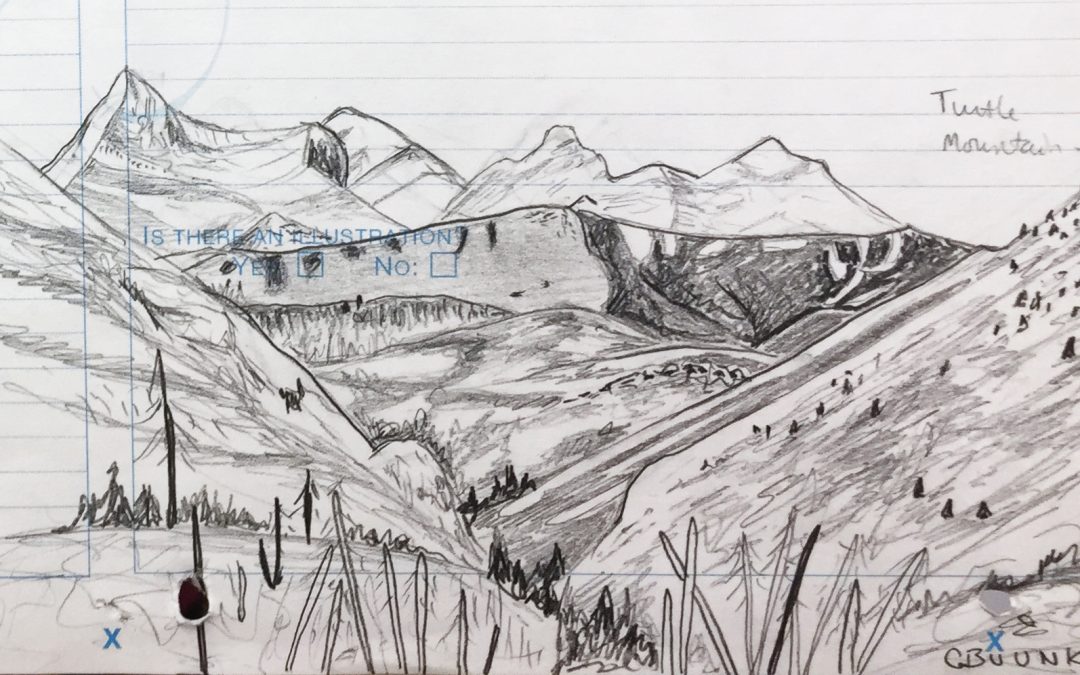

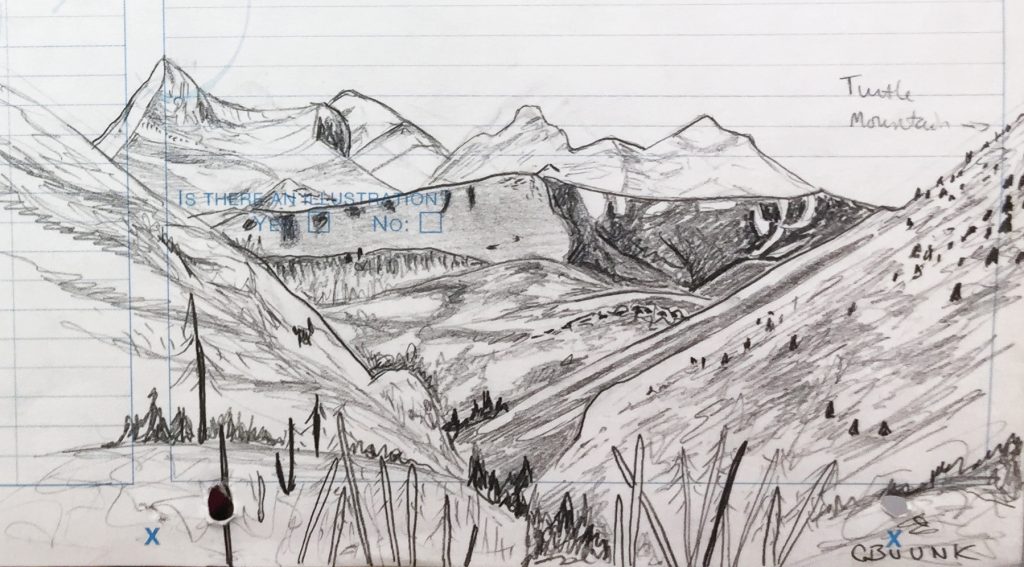

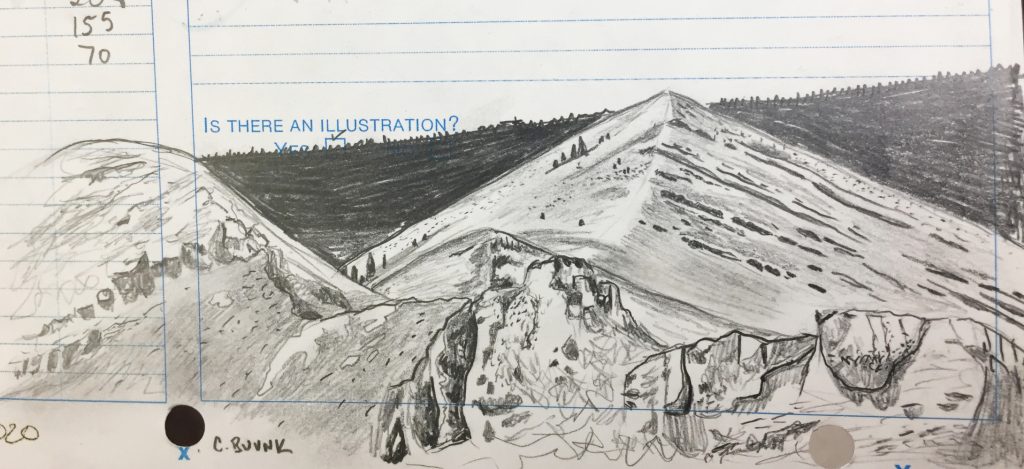

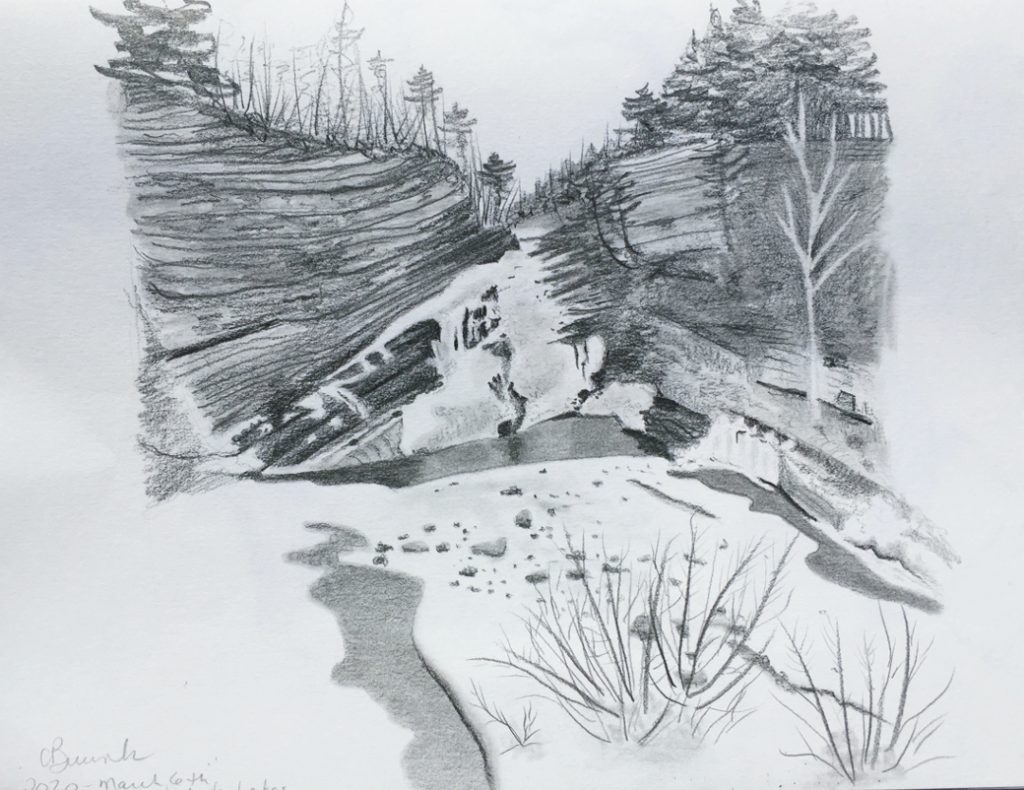

There is a little box on the bottom right hand side of the Mountain Legacy Project field note sheets that I took as an invitation to sketch the landscape. I took every opportunity to sketch the mountains in our 2019 field season. My fellow team members—Sonia Voicescu, James Tricker, and Charles Hayes–were gracious enough to let me note-take as part of fieldwork, which gave me the opportunity to draw. I have been making art for as long as I can remember. Alongside student and professional activities, I have identified as an artist for at least the second half of my life, and unabashedly in the last several years. My artistic focus has shifted to natural history illustration in the last year, which was in part inspired by the time I spent drawing out in the field with the MLP. There is something about drawing that pulls me into a different frame of awareness that also helps my graduate studies in the School of Environmental Studies. My inevitable drift to art helped convince me to centre my master’s research project on how images shape our view of the landscape, particularly the ways in which people working in Waterton Lakes National Park connect to images portraying ecological change through the last century such as the 2017 Kenow Wildfire.

In Field Notes on Science and Nature, scientist and artist Jenny Keller (2008) asks, “Why Sketch?” She discusses the importance and relevance of taking visual field notes in addition to written notes, advocating that drawing gives you an opportunity to understand your subject better and capture things that written notes or photographs cannot. Keller was writing mainly about subjects that are much smaller than mountains, such as fish, flowers, or insects, but I apply similar principles to drawing mountains: sketching provides space to understand and connect to the mountain in a deeper way.

Keller encourages people to give it a try even though they may not consider themselves a skilled artist. An elementary school teacher of mine gave me the best artistic advice, and the only artistic advice I have adhered to faithfully in my life – “Draw what you see, not what you think you see.” Drawing in the field demands that you pay attention to your subject to understand all its subtle details. Keller calls sketching an “observational tool” (2008, p.161), and explains, “The creation of an accurate drawing requires a systematic approach, patient observation, an openness to unforeseen possibilities, an ability to regard a topic from a variety of perspectives, a willingness to pay attention to both the exciting and the mundane,” and building upon what my elementary school teacher said, requires “the deliberate setting aside of preconceived ideas” (pp.184-185).

“Draw what I see.” Okay. It was only a little bit daunting when what I saw was a million tiny ridges, cliffs, snow packs, and trees. But another thing I’ve learned over the years is that it is up to the artist to decide before they start how much detail they want to include.

The limiting factor in creating my sketches – and adding detail – was time, which is no different than trying to find the time in my day-to-day life to create art. The most elaborate sketches I made were ones where we were waiting for the helicopter to come. A little part of me cheered when we would hear on the radio that the helicopter had a couple errands to run before getting us! Otherwise, it was usually a mad dash to capture what I was seeing.

In revisiting the sketches I made last summer I can see significant improvement, which I hope is an encouragement for anyone feeling hesitation about whether to start sketching. Charles, James, and Sonia all participated in field sketching at some point and it definitely brought smiles to all our faces and joy to our days. I am not out in the field this year but I challenge the 2020 crew to add some more sketches to the MLP fieldnote gallery.

What is the value of these sketches? That remains to be seen. But a part of me hopes that in 100 years or more, someone finds them and feels inspired to sit, sketch, and appreciate the mountain for what it is.

Reference:

Keller, J. (2018). Why Sketch? In Canfield, M.R. (Ed.), Field Notes on Science & Nature (pp.161-185). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.