By Mary Sanseverino, June 23, 2020

Just last week on June 16 two intertwined articles, both about landscape change in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, came out. Both were published under the auspices of the Nature Research family of journals, one of the world’s leading multidisciplinary science organizations.

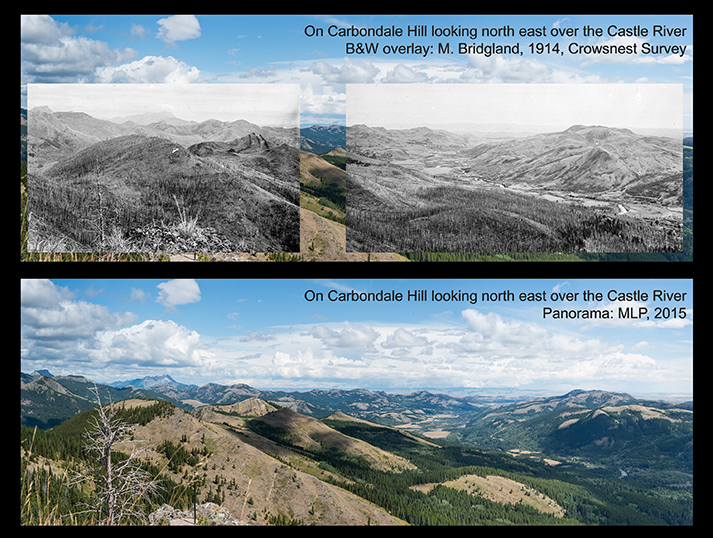

The first, entitled “A century of high elevation ecosystem change in the Canadian Rocky Mountains“, came out in Nature – Scientific Reports. The authors, Andrew Trant, Eric Higgs, and Brian Starzomski, present a compelling look at how Canadian Rocky Mountain landscapes are shifting. Using novel information contained in historic / modern photo pairs their quantitative analysis examines treeline advance, changes in tree density, and shifts in growth forms from krummholz to trees.

The second is called “Raising a glass to my long-dead collaborators!“. This article is a little bit different. It appears in Nature Research Ecology & Evolution Community – Behind the Paper. In it author Andrew Trant pays homage through personal reflection to the scientific surveyors who worked in the same landscapes – many over 100 years ago – as Andrew does today.

In working with the photos, field notes, and maps so expertly prepared by surveyors and engineers long gone Andrew, his students, and colleagues join all of the researchers involved in the Mountain Legacy Project in standing on the shoulders of giants.

A century of high elevation ecosystem change

The material contained in “A century of high elevation ecosystem change in the Canadian Rocky Mountains” is fascinating. In it Trant, Higgs, and Starzomski analyze 81 high-resolution historic/modern image pairs from the Canadian Rockies. Their study sites range from the Willmore Wilderness north of Jasper National Park, down to Waterton National Park at the Alberta/Montana border.

Their work establishes quantitative evidence of alpine treeline advance, conifer densification, and tree structure change. The MLP images in the slideshow below illustrate some of key findings in the paper.

Raising a glass to my long-dead collaborators

In “Raising a glass” Andrew Trant takes us behind the scenes, showing something of what it was like to create the ecosystem change paper. He also gives us an opportunity to walk with him as he walks with his historic collaborators – the scientific surveyors, accomplished mountaineers, and expert photographers who worked as Dominion Land Surveyors.

In the article Andrew gives us a glimpse into the work of Morrison Parsons Bridgland. He was a Dominion Land Surveyor of renown and a formidable force in the Canadian mountain west. Many MLP field teams, researchers, and historians have wondered, as Andrew does, what it might be like to sit down with “Morrie” and compare notes.

Here’s to the legacy these giants left us – may we use their work wisely, ask hard questions, and leave a legacy half as rich for others to carry on when we are gone.

More information

Mapper of Mountains: M.P. Bridgland in the Canadian Rockies, 1902-1930

Mapper of Mountains follows the career of Dominion Land Surveyor Morrison Parsons Bridgland, who provided the first detailed maps of many regions of the Canadian Rockies.

The Mountain Legacy Explorer. Explore MLP’s historic and modern image collection in its geographic context.

The Nature Research family of journals, communities, and report. Click on the menu icon to see all their publications.

The Mountain Legacy Project on Facebook – follow for quick updates.