By Claire Wright

Plagued by heat, smoke, rain and strong winds, the 2023 MLP field season almost didn’t happen. It was late August when the monotony of waiting for improved conditions finally broke and a whirlwind of activity led to a surprisingly productive spell of repeat photography.

*******

The first rule of fieldwork is that nothing goes to plan. MLP crews prepare for months before travelling to the Rockies, and then hours each night before a mission poring over survey images, trip reports, and weather apps. But they must also prepare for plans to go awry, as schedules turn on their head and objectives change at the last minute. It often requires deep patience to wait for conditions to be right – for snow to melt, smoke to lift, and rain to clear. The 2023 crew navigated these realities throughout the summer with amazing humour, grit, and tenacity.

Following a land camp with the Stoney Nakoda Nations in early August (stay tuned for an upcoming post), Eric, Shima, and I drove to Waterton Lakes National Park, where we arrived to sweltering heat. With five years of MLP photography work already accomplished in the park, there are very few stations left to repeat – and those that remain are not low-hanging fruit. In light of the weather, we decided that our larger objectives were too ambitious to take on. Luckily, there was other work to be done. Through the tireless efforts of long-time MLP partner Rob Watt, we had acquired images captured by the North American Boundary Commission in 1874! It was a powerful experience retaking the photographs 150 years later, to find rocks in the foreground that hadn’t moved despite the vast changes visible in the landscape around us.

Crandell Mountain as seen from the current site of the Prince of Whales Hotel captured by the North American Boundary Commission in 1874 (left) and repeated by the Mountain Legacy Project in 2023 (right).

Crandell Mountain as seen from the current site of the Prince of Whales Hotel captured by the North American Boundary Commission in 1874 (left) and repeated by the Mountain Legacy Project in 2023 (right).

After days of ground-level work, the heat finally broke. I was feeling optimistic as I drove back from an errand in Lethbridge. With the cooling weather, we could attempt the more challenging stations, and there were even some rumours swirling around the use of the beautiful A-Star helicopter sitting outside the park offices. Owing to the unique topography of the prairie-mountain interface in that part of the Rockies, I could see Waterton’s peaks from quite a distance on the highway. It looked like an afternoon storm brewing based on the dark clouds sitting atop the mountains. Travelling closer, I realized that it wasn’t a storm after all. The smoke from Canada’s worst wildfire season on record had finally reached us. Billowing black clouds settled over the park, preventing meaningful photography work for several days.

Clouds of wildfire smoke settling behind the research house Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo: Eric Higgs.

Clouds of wildfire smoke settling behind the research house Waterton Lakes National Park. Photo: Eric Higgs.

I was beginning to despair, but just as I thought my patience would run out, the smoke cleared, the weather improved, and the park approved time in the helicopter. After so many days of waiting, we finally dove into action. Now was the time to think on our feet and be ready for plans to shift by the minute. My teammates, James and Sarah, were amazing at supporting the work and assisting me in the field. Thanks to generous support from the park, not only through the use of the machine but also with volunteers, we repeated six stations in two days!

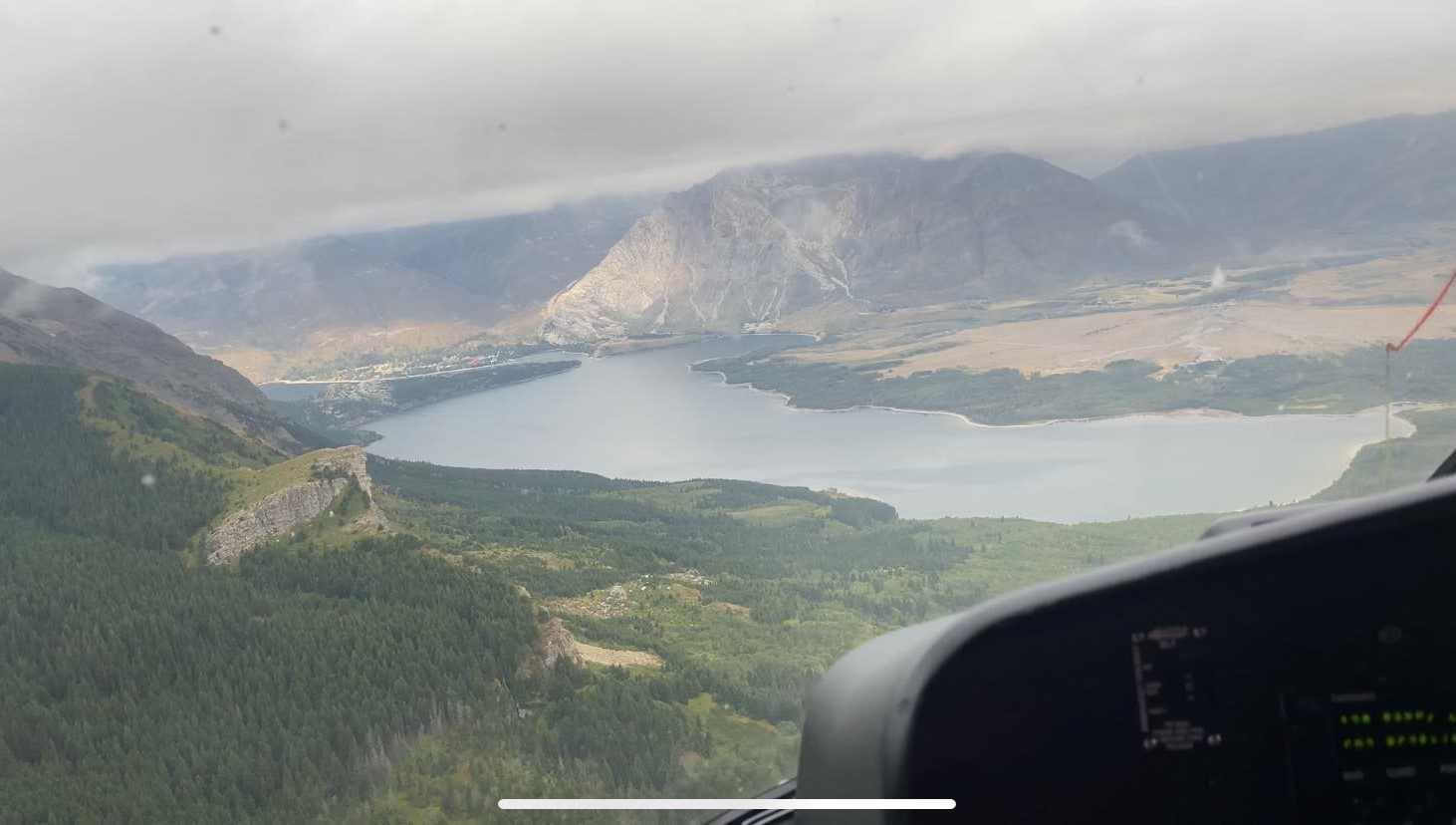

Waterton townsite and Mount Crandell from the helicopter.

Waterton townsite and Mount Crandell from the helicopter.

At the end of our stay in Waterton, we had the pleasure of joining Alvin First Rider from Kainai Nation to repeat two survey stations on the Blood Timber Limit. We had a big group, including our point person from the park, the remarkable Kim Pearson. It was fascinating to look at the changes that a century of fire suppression combined with bison extirpation and climate change had wrought on the foothills and to hear Alvin’s insights into plans for future stewardship under Blackfoot leadership.

Blood Timber Limit and adjacent parkland from Stn. 108 Belly River. Originally photographed by M. P. Bridgland in 1914 (left) and repeated by the Mountain Legacy Project in 2023 (right).

Blood Timber Limit and adjacent parkland from Stn. 108 Belly River. Originally photographed by M. P. Bridgland in 1914 (left) and repeated by the Mountain Legacy Project in 2023 (right).

From Waterton, I drove up to Jasper National Park for my last week of the season. Once again, smoke and wet weather kept me from many of my objectives. Nevertheless, Sarah and I managed to get out to a station overlooking the recent Chetamon fire. I also joined Nicholas Lai from the whitebark pine crew for a day in the forest, taking photographs and searching for trees.

Panorama of the aftermath of the 2022 Chetamon fire in Jasper National Park. Historical images captured by M. P. Bridgland in 1915 (bottom) and repeated by the Mountain Legacy Project in 2023 (top).

Panorama of the aftermath of the 2022 Chetamon fire in Jasper National Park. Historical images captured by M. P. Bridgland in 1915 (bottom) and repeated by the Mountain Legacy Project in 2023 (top).

Despite the many challenges of the field season, patience and perseverance won out. With support from many people within the MLP lab and at Parks Canada, we visited and repeated 13 photostations with plenty of wonderful conversations and adventures along the way. None of this would have been possible without carefully researching the stations in advance, setting flexible objectives and building relationships with our partners, proving that all the planning pays off, even when nothing goes to plan!