The Mountain Legacy Project (MLP) now boasts over 10,000 repeat photographs collected over close to three decades. Our repeat photography involves intense fieldwork across Canada’s mountain landscapes. In the following series of blog posts, we turn our focus “behind the scenes” of image collection – exploring the fun, mundane, exciting and at times disheartening experiences of climbing mountains to recapture historical photographs. In this first post, we take a look at a day-in-the-field by a team working in Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta.

***

By Claire Wright and and Daniel Brendle-Moczuk | December 13, 2022

Our team consisted of Claire Wright, a graduate student with MLP at the University of Victoria, Daniel Brendle-Moczuk, the geospatial librarian at the University of Victoria and Laura Tuner, a visiting PhD student from the University of Nottingham. Our target was a craggy but majestic looking peak named Mt Alderson by Dominion Land Surveyor, Morris Bridgland. Prominent, and known for its panoramic views, Alderson lies just north of the US border, in Waterton Lakes National Park. It was our first objective as a crew in 2022, but as with all MLP fieldwork, our efforts began weeks before the ascent, in office spaces and research labs, where the original photographs were examined and possible routes up our target mountains determined. Going into the field season at Waterton, we had eight priority stations with an additional eight back-up locations. For each objective, we studied maps, guidebooks and trip reports to plan our approach. We also relied heavily on notes from previous field crews to help us plan our outings (Mt Alderson was a first-time objective for MLP, so we couldn’t rely on details from previous MLP ascents).

Repeat image from summit of Mt Alderson taken July 9, 2022

Repeat image from summit of Mt Alderson taken July 9, 2022

Although we had a tentative schedule worked up for the duration of our six-week stay in Waterton, this was quickly flipped on its head by reports of lingering snow following an abnormally cool and wet spring. After consulting with the knowledgeable park staff, we determined that Mt Alderson was a promising first objective while we waited for the snow to finish melting out. Using the beta (i.e., the maps and past trip reports) we collected earlier in the year, we planned our route: a 26 km roundtrip hike to the summit with approximately 1000 m of elevation gain.

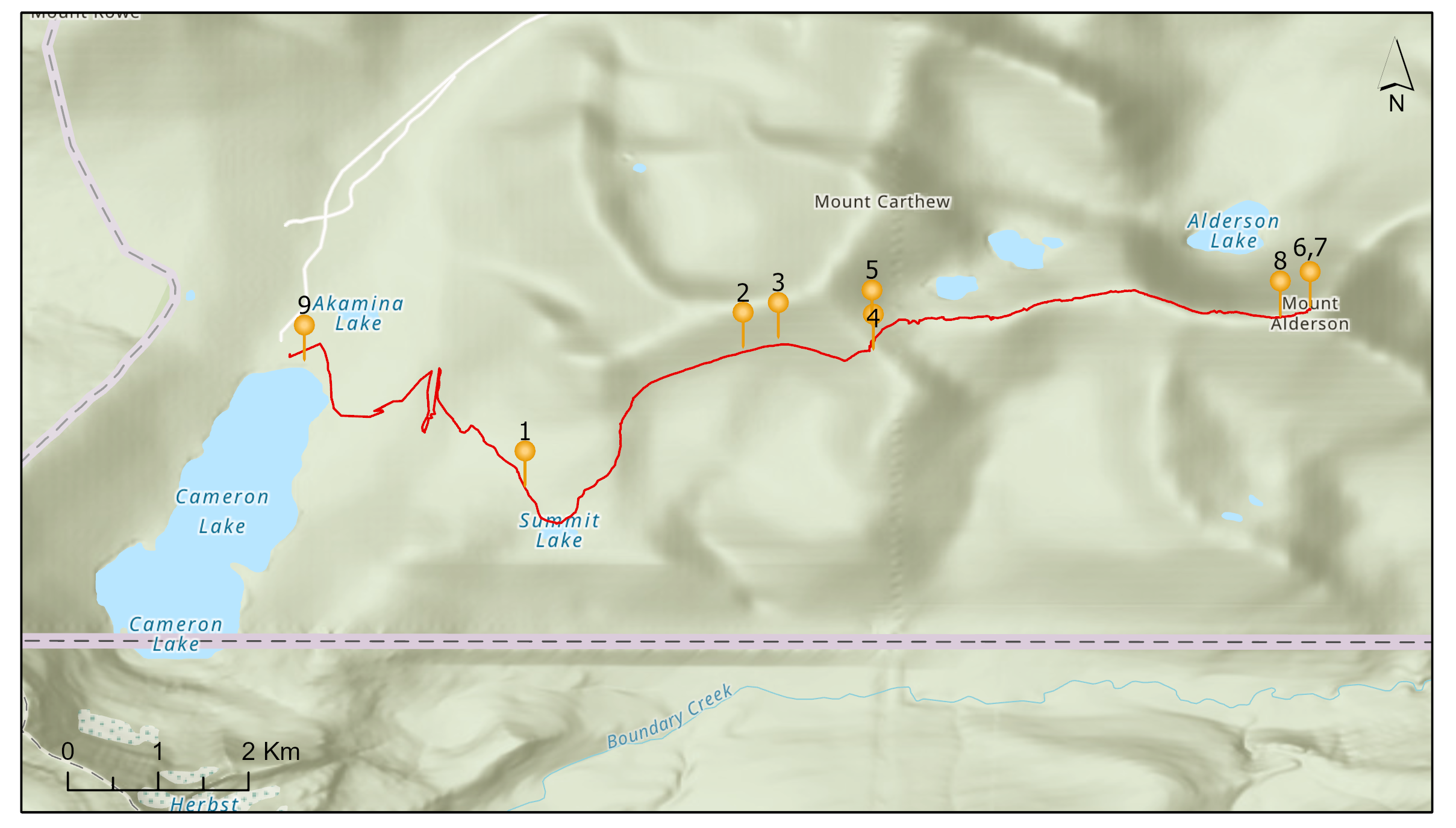

Route map (numbered positions correspond with images below)

Route map (numbered positions correspond with images below)

Still more preparation remained. The evening before a repeat-photography outing is spent carefully checking equipment (camera, radios, first-aid) and expectantly going over multiple weather forecasts – for us, this included the Environment Canada forecast for Waterton Lakes Park, the 2.5 km High Resolution Deterministic Prediction System model, elevation 1930m, forecast for the Mt Alderson area approximately 6km from the Waterton weather station, and the 3km NOAA High Resolution Rapid Refresh. Each predicted a high-pressure system that would bring sunshine and relative warmth, along with some wind, but little chance of precipitation – ideal conditions!

As final preparation, our team once again turned to the surveyor photographs, carefully studying the high-resolution digital copies of the original images taken by Allison B. Grant in 1953. We did so to confirm camera location and orientation. Thankfully the Grant photographs were all in landscape orientation as some surveyors, such as Bridgland, switched between landscape and portrait (but that confusion belongs to another fieldtrip and another story). We also used Google Earth to confirm that the images were in fact captured from the coordinates that we anticipated. All that remained was to get a good night’s sleep.

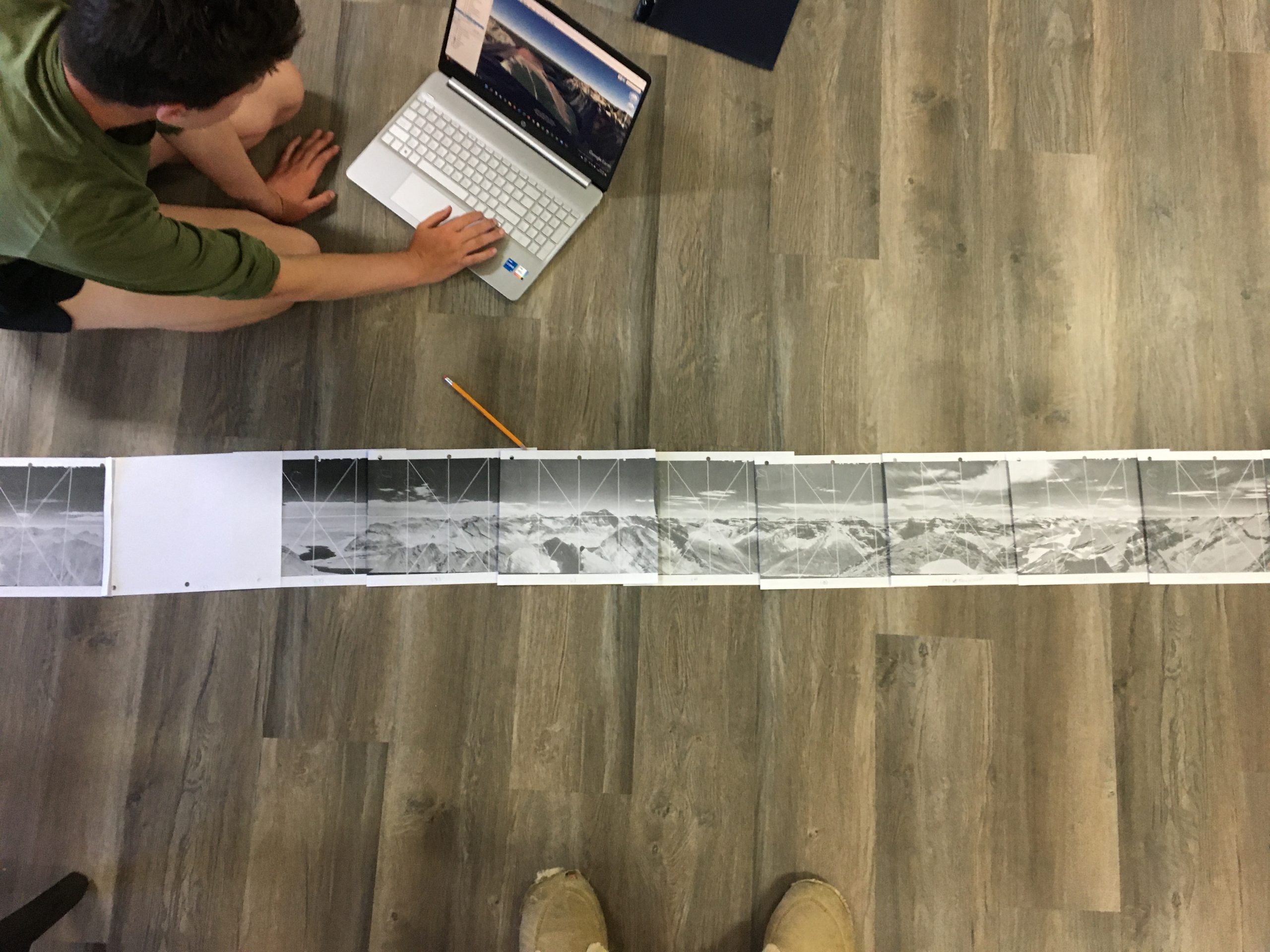

Going over the images the night before

Going over the images the night before

On Saturday July 9, we woke early and left the Waterton research house by 6:15am, driving up Akamina Parkway to the Cameron Lake (1650m) day use area from where we headed out on the Summit/Carthew-Alderson trail. Our packs were loaded with a FujiGFX100 camera, tripod, other camera paraphernalia, azimuth and wind instruments, our safety gear such as emergency bivy shelters, rope, extra layers and plenty of food and water. In short, our packs were heavy! In less than an hour of hiking up switchbacks, we had a good view across the Canada-US border to Mount Custer and Lake Nooney.

View to Mount Custer and Lake Nooney (position #1, 1960m (49.01028, -114.02774))

View to Mount Custer and Lake Nooney (position #1, 1960m (49.01028, -114.02774))

Another hour or so later took us past Summit Lake travelling through areas burned in the Kenow wildfire of 2017. Once again, we had views into the US, glimpsing Chapman Peak and Lake Wurdeman, Montana.

View to Montana (position #2, 2170m (49.02064, -114.01147))

View to Montana (position #2, 2170m (49.02064, -114.01147))

At lower elevations we were warm, but this would soon change as we navigated the ridge overlooking Carthew Lakes; here, hot tea and snacks out of the wind were reviving. The trail lost a bit of elevation toward the lakes before we climbed up a very steep slope to attain the final ridge towards Alderson.

Moving along the trail (position #3, 2310m (49.02049, -114.00175))

Moving along the trail (position #3, 2310m (49.02049, -114.00175))

Taking a break to snack (position #4, 2200m (49.02136, -114.00884))

Taking a break to snack (position #4, 2200m (49.02136, -114.00884))

From reading other trip reports, we knew there were two Class 3 downclimbs through rocky sections. Although all of us were comfortable on technical terrain, we chose the longer and safer route involving a couple of detours down the ridge. We also knew to expect a prominent false summit with some scrambling. Following a set of cairns, we navigated the false summit – but all did not go smoothly. Claire’s helmet fell off her bag and rolled away down the mountain. Moments later, her bear spray caught on the rock and set-off, the safety having been lost some time earlier in the day. Thanks to 70 kph winds gusting from below, the spray was swept up and blown into Claire’s face! After much cursing and eye-washing, the team decided to continue to the summit and attempt the station.

Bear spray incident occurred on scree slope to the upper right (photo at position #5, 2345m (49.02229, -114.00185))

Bear spray incident occurred on scree slope to the upper right (photo at position #5, 2345m (49.02229, -114.00185))

We reached the summit around noon – now the real work could begin. Using our approximate coordinates and the historical images, we moved around until we felt we were in the correct location. This involved picking out features in the images and making deductions based on their relative positions. We then set up the tripod and secured the camera to a rail on top. We spent a good length of time adjusting the height and location of the tripod, comparing what was visible through the camera viewfinder with the historical images until everything lined up perfectly. Finally, we were ready to start taking photos.

Getting the tripod just right (position #6,7, 2692 m (49.02367, -113.96916))

Getting the tripod just right (position #6,7, 2692 m (49.02367, -113.96916))

While we homed in on the camera position, we also prepared field notes describing our approach to the station and the conditions we encountered. We recorded weather data using a Kestral 3500 Pocket Weather unit including temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity. Once confident about the location for the tripod, we used a compact shoot and point camera to photograph our set-up to make it easier for future researchers to re-find the station. With care and precision, we repeated a total of 12 historical images, spending around 2.5 hours on the summit.

Getting the shots (position #6,7, 2692 m (49.02367, -113.96916))

Getting the shots (position #6,7, 2692 m (49.02367, -113.96916))

Heading down slope after repeat photography (position #8)

Heading down slope after repeat photography (position #8)

Yikes! Scat found on our way out (position #9, 300m from parking lot!)

Yikes! Scat found on our way out (position #9, 300m from parking lot!)

When we were done at the top, we retraced our steps on the hike out, arriving back at the research house at 7:15 pm. Our work was not yet finished – we still had to unpack, download the images from the camera, complete our field notes, clean and store gear, and prepare to do it all over again. We wouldn’t want it any other way!