As the new academic year begins, we’re highlighting a different branch of the Visualization Lab’s work.

This post features the work of Shima Tajarloo, a PhD student in Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria, and MLP-er since 2022! With a background in architecture and landscape architecture, Shima explores the ecological restoration of urban ecosystems through architectural practice, emphasizing regenerative design principles. In collaboration with Christine Lintott Architects (CLA), she is developing pathways and tools to narrate the story of place, drawing on historical archival data and bridging the gap between academic research and design practice.

By Shima Tajarloo, University of Victoria

At the Visualization lab, much of our work begins with careful observation, whether through repeat photography of mountain landscapes or through on-the-ground exploration of ecological change. While this often takes us to alpine environments, our lab also engages in collaborations that bring that same spirit of inquiry into contemporary, designed landscapes. Through our collaboration with Christine Lintott Architects Inc. (CLA), an architectural practice based in Victoria, British Columbia, we explore the intersection of ecological restoration and regenerative ecological design, asking what it really means to restore ecological processes in project sites, and how design can act as a bridge, not a barrier, to that return.

A large part of our work is about challenging human-centric models of development. Instead, we aim to ask better questions: What stories do places hold beneath their paved surfaces? What ecological functions or processes have been lost and what might be restored? What happens when we shift from seeing design as something we impose onto a place, to something that emerges through careful listening?

In practice, that means working across disciplines. Our collaboration provides a space to challenge assumptions, share knowledge across ecological and design domains, and test new ways of thinking not just on paper, but in place.

Revisiting Landscapes: Post-Occupancy Evaluation at Power To Be

Early in our collaboration I began asking: what really happens once the ribbon is cut? When a design begins to breathe, plants take root, rainwater carves its path, and people make the place their own—how does the landscape respond? Does it embody the ecological and social intentions we set out with, or does it surprise us in unexpected ways? While post-occupancy evaluation is a familiar tool in architecture, it remains relatively new at the scale of landscapes. Yet it offers a powerful way to listen: revealing stories, surprises, and lessons we might otherwise miss.

Figure 1: Site visit to Power To Be Basecamp, with CLA crew and our research crew from university of Victoria., March 2024. Photo by Dr.Eric Higgs.

We approached Power To Be, an inclusive outdoor activity centre on a restored golf course near Prospect Lake in Victoria, as a case study. Designed by CLA and MDI Landscape Architects, the site was rich in ambition: to regenerate damaged ecosystems, to celebrate Indigenous presence, and to make nature more accessible to everyone. It felt like the perfect place to ask: how do we measure what matters?

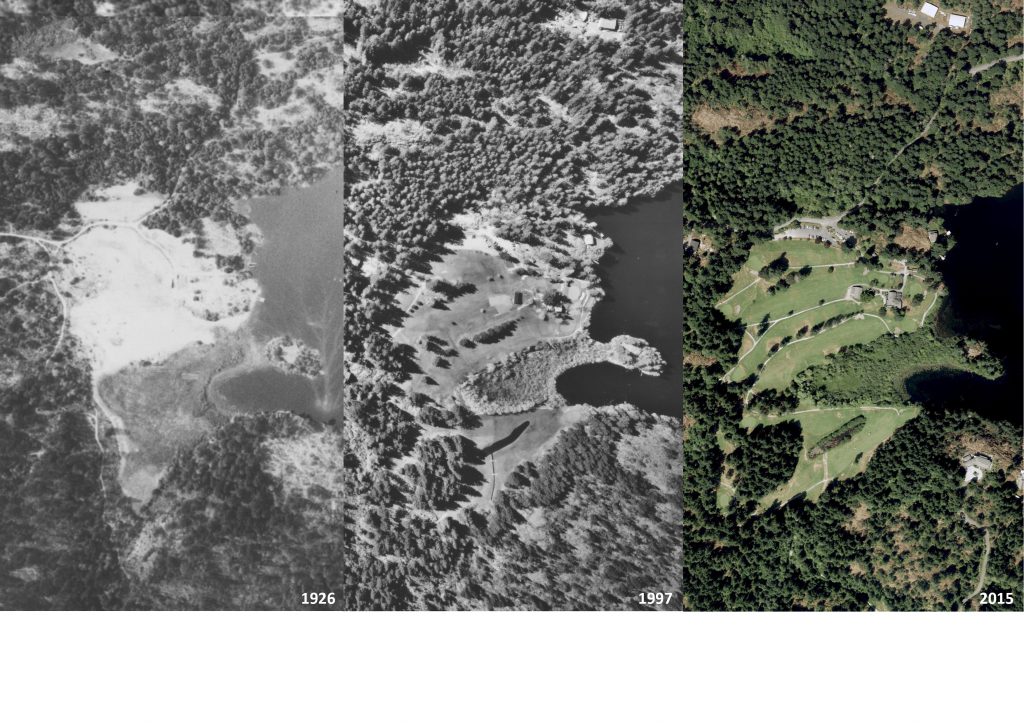

Historic photographs and maps of the site ranging from its early days as farmland to its use as a golf course from 1964 to 2015 offered a valuable lens to understand its layered history and ecological past. These visual records helped ground our evaluation in the site’s longer ecological narrative and supported our work of observing change over time.

Figure 2: Aerial photographs showing the transformation of the Power to Be site over time.

The process began with reaching out to the Power To Be team, who generously welcomed us. Our research group, along with the CLA team, visited the site multiple times over the course of a year. We walked the trails, observed rain gardens, asked questions, and heard stories from staff and participants. Slowly, a different picture of the project began to emerge, not just as a designed project anymore, but as a living, evolving system. This study was supported through the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Case Study Investigation program, which brings together academics and practitioners to document the performance of exemplary landscape projects. You can read the full Power To Be case study brief on the Landscape Performance Series website.

Figure 3: Tour of the site with Jason Cole CEO of Power To Be Basecamp, March 2024. Photo by Dr.Eric Higgs.

We gathered data through a variety of methods:

- Team site visits to walk the landscape and reflect on its current state.

- One-on-one interviews with staff, asking how the site shapes their day-to-day experiences.

- A focus group with program participants, where we used engaging tools to explore how the landscape made them feel.

- On-site engagement activities during a “Have A Go” day, where participants shared reflections directly tied to their experience of place.

- Landscape attribute surveys to document vegetation, surface conditions, and other ecological indicators.

- Seasonal visits to observe how the site changed across weather, use, and time.

Each visit added nuance. We noticed how the summer sun challenged the existing shade cover. Some planted areas thrived, while others struggled to adapt. We saw first-hand what worked and what didn’t in terms of accessibility, as participants navigated pathways, gathering areas, and natural features. Trade-offs in design decisions became clearer on the ground. Through these observations, we were reminded that design is just the beginning. Occupancy, and the ongoing dialogue between people and place, is what gives a place its true test.

The Value of Going Back

One of my biggest takeaways was this: repeatedly walking a site, after it has been handed over to its users, is invaluable. Each return reveals something new; how people experience place, where they pause, how species thrive on site, the relationship and stewardship that forms through land and people, what the site gives back or still lacks. This kind of feedback loop is essential if we want to move from static, one-time interventions to dynamic, responsive landscapes.

The Power To Be evaluation taught us to expand our methods. Yes, we used tools to assess shifts in ecosystem dynamics, but just as importantly, we listened, to the land, to its occupants, and to the unfolding stories and patterns between them. Stories that don’t always show up in conventional metrics but only when you’re curious enough to observe, walk the land and listen with curiosity and care. Recognizing the value of going back, CLA is considering how revisiting projects after completion can become a more intentional part of their practice; ensuring that lessons learned in occupancy continue to inform and strengthen future designs.

Figure 4: Shima Tajarloo and Hayley Johnson filling out landscape attribute surveys for different landcover types to understand ecological function. Power To Be. Basecamp, July 2024.

Looking Forward: Visiting Sites in Early Design

While the Power To Be case study focused on post-occupancy evaluation, our collaboration has since expanded to visiting future project sites in their early design phases. These pre-construction visits offer a different kind of opportunity, to listen to the land before lines are drawn and construction begins. At a recent site walk for the Millstream project, a residential development underway in Langford, I joined Hayley Johnson from CLA to observe how ecological stories and patterns can emerge in the site’s edge conditions, pointing to new possibilities for ecological restoration.

These early-stage visits help us ask different questions: What ecological processes are already at play? What’s being overlooked in the default approach? How can we shift from “business-as-usual” scenarios to a design approach that is more regenerative and ecologically informed?

Figure 5: Walking the site to understand edge conditions, Millstream Residential project site visit, June 2025. Photo by Shima Tajarloo.

Figure 6: Walking the site to understand edge conditions, Millstream Residential project site visit, June 2025. Photo by Hayley Johnson.

Reflections

Site visits, whether after construction or before design, create opportunities to notice what drawings alone can’t reveal and remind us that landscapes are not static outcomes but evolving systems shaped by people, climate, and ecological processes. Each visit is a chance to notice patterns, learn from surprises, and adapt our thinking. These projects are more than just buildings or landscapes, they’re living systems. And systems, we’re learning, reveal their patterns only when you walk them, again and again!

Moving forward, we’re excited to share more about our explorations, methods, and site stories. Stay tuned for future posts, where we’ll share more about site visits, design tools, and the evolving role of landscape performance in ecological design.