By Alina Fisher

I felt so confused. Not only was I driving on the wrong side of the road, but I also spied a unicorn ahead of me in the valley. I could barely believe my eyes. We were travelling along a narrow gravel road aside the River Freshie. As it wound towards the Glenfeshie Estate, I finally recognized that it wasn’t a unicorn at all, even though that is the official animal of Scotland. Yet what I saw was just as magical – three gorgeous white horses, as majestic as the famed Shadowfax from Lord of the Rings. There was good reason fantasy was on my mind: I was arriving at an extraordinary place.

*******

Coat of Arms, Mary Queen of Scots (image courtesy the National Trust for Scotland)

Coat of Arms, Mary Queen of Scots (image courtesy the National Trust for Scotland)

Highlands Compared

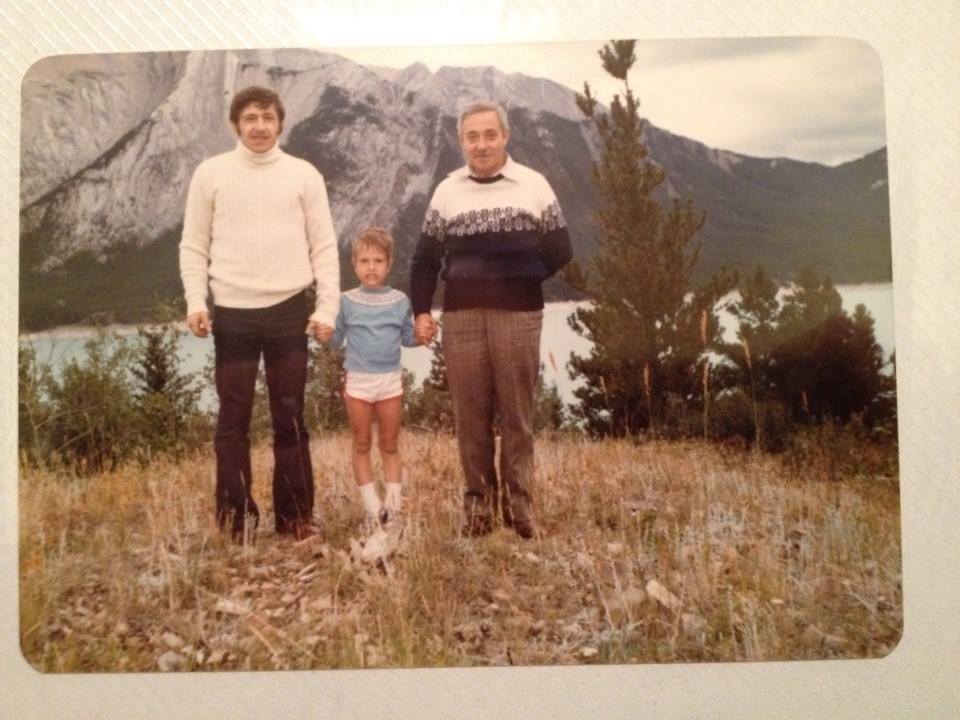

I came to the Cairngorms National Park in the Highlands of Scotland with my husband and colleagues to observe the rewilding efforts there. Rewilding, a conservation approach aimed at restoring ecosystems to their natural state by reintroducing native species and allowing natural processes to take place, has gained significant attention worldwide. While the guiding principles remain the same, the implementation of rewilding efforts can vary greatly depending on the context. My visit to Glenfeshie not only revealed the possibilities and complexities of rewilding but provided an intriguing contrast to a more familiar landscape closer to home, the Rocky Mountains.  Me as a child, my father and Otata in Banff National Park

Me as a child, my father and Otata in Banff National Park

Glenfeshie, Scotland: Rewilding the Highlands

In the heart of the Cairngorms National Park in Scotland lies Glenfeshie, a landscape once dominated by intensive land use practices such as sheep farming and deer stalking. In contrast to Crown-owned national parks in Canada, the Cairngorms National Park lands are predominately owned by individuals or trusts, comprising over 150 holdings ranging in size from 100 to 40,000 ha. Any large-scale rewilding or conservation effort requires the cooperation of multiple landowners around a common cause. Amidst these challenges, the Glenfeshie estate has, in recent years, become a beacon of hope for rewilding efforts in the UK.  Caledonian Pines in Glenfeshie

Caledonian Pines in Glenfeshie

The Wildland Limited project in Glenfeshie has focused on restoring the ecosystem by reintroducing key species such as beavers, protecting Caledonian pine trees and controlling red deer. By allowing natural regeneration of native woodlands, Glenfeshie has seen a remarkable transformation, with the return of biodiversity and the re-establishment of ecological processes. As an example, the diligent work of beavers helps to thin out overcrowded saplings, allowing the remaining trees to grow and flourish. This reduces erosion and stabilizes watercourses which also minimizes flooding. Even the temporary, localized flooding created by beaver dams, which was once considered to be a nuisance, allows for the return and re-establishment of endangered wetland birds. It’s amazing how much can heal with the reintroduction of one species allowed to resume its natural activities. These collaborative efforts between conservation organizations, landowners, and local communities demonstrates the power of rewilding to revitalize landscapes and reconnect people with nature. Glenfeshie serves as a model for rewilding projects across the UK, showcasing the potential for restoring wilderness in even heavily modified landscapes.

Outside of Glenfeshie, the Cairngorms National Park has actually been home to a rewilding experiment of a sort for over seven decades. Although caribou had been in Scotland before, they went extinct nearly 800 years ago. In the 1950s a Lappish man, Mikel Utsi, and his wife Dr. Ethel John Lindgren, recognized the potential for reindeer (domesticated caribou) to thrive in the area and shipped a small group of reindeer from Sweden. Today it remains the only free-roaming herd in Scotland.  Herd of reindeer, the Cairngorms National Park

Herd of reindeer, the Cairngorms National Park

Banff Bison Reintroduction, Canada: Restoring an Iconic Species

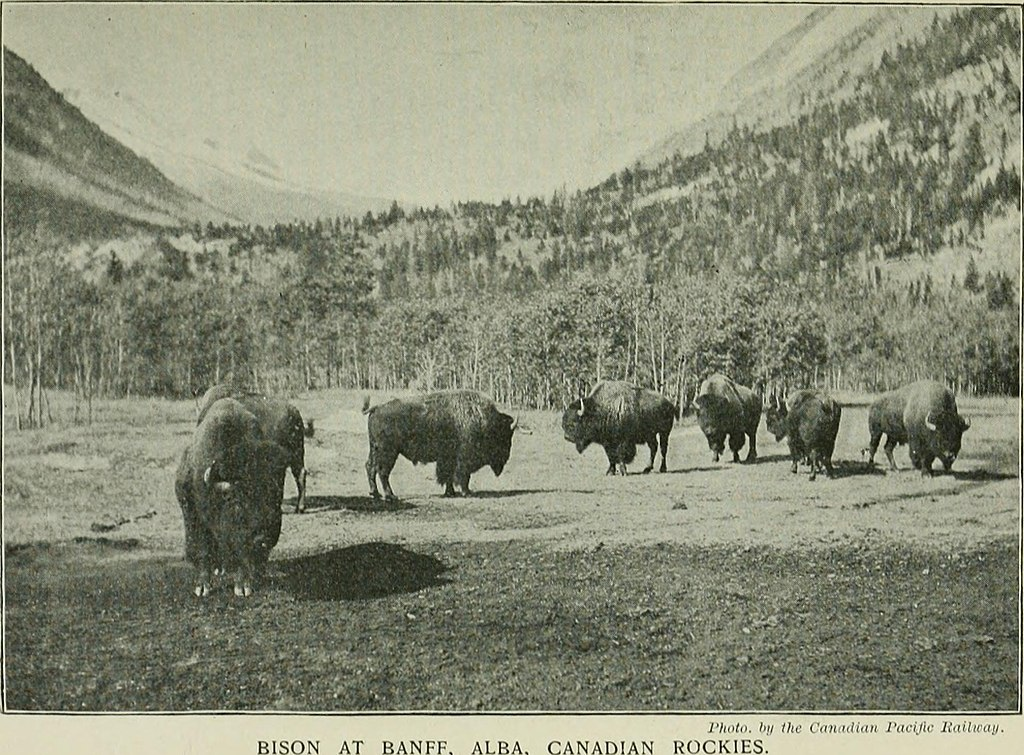

Growing up in Alberta, I spent a lot of time wandering about in Banff National Park on foot, on skiis, and on snowshoes – enjoying not just the beautiful vistas but inspiring glimpses of the native wildlife. From valley bottom to rugged peaks, it never dawned on me that a large and conspicuous species was missing from that landscape. Bison, once a keystone species of the North American prairies, were extirpated from Alberta and Saskatchewan in the 1880s due to overhunting and habitat loss. It had been a long time since their hoof-falls etched the soil or their bodies made wallows.  Bison herd in Banff National Park, ca. 1904 (image courtesy Canadian Pacific Railroad on Flickr)

Bison herd in Banff National Park, ca. 1904 (image courtesy Canadian Pacific Railroad on Flickr)

However, in 2017, during Canada’s 150th anniversary, 16 plains bison were reintroduced to Banff National Park as part of a collaborative effort between Parks Canada, the Stoney Nakoda Nations, and conservation organizations. This historic reintroduction aimed to restore the ecological role of bison in the landscape, enhance biodiversity, and promote cultural connections with Indigenous peoples.  Bison herd in Banff National Park, ca. 2021 (image courtesy Parks Canada)

Bison herd in Banff National Park, ca. 2021 (image courtesy Parks Canada)

Since their return, the bison have begun to roam freely across the 1,200 km2 reintroduction zone, shaping the landscape by grazing and creating habitat for other species. In 2023 the bison herd had grown to over 100 animals, a far cry from the thousands that once roamed Alberta, but heartening all the same. The Banff bison project exemplifies the importance of large-scale rewilding initiatives in preserving iconic species and restoring ecosystem function. Much like efforts at the Cairngorms National Park, the project emphasizes the importance of bringing together different stakeholders and communities in order to realize a successful outcome.

Looking Ahead

Though I didn’t get to see a Scottish wildcat during my visit to the Highlands, I did get to see reindeer, unicorn-impersonating horses and found the “Valley of the Granny Pines” – one of a mere handful of the ancient Caledonian forests that exist to this day (only 1% remain). In Glenfeshie, the focus is on restoring a fragmented landscape and balancing conservation objectives with traditional land uses such as sheep farming and deer stalking. In Banff Canada, the reintroduction of bison is a bit more “hands on”, requiring careful management to mitigate conflicts with tourism and ensure the long-term viability of the herd. Rewilding in Glenfeshie and the Banff bison reintroduction project showcase the power of conservation to restore ecosystems and reconnect people with nature. By learning from these diverse examples and collaborating across borders, we can work towards a future where landscapes thrive and biodiversity flourishes. Doing so will take political will, thoughtful engagement and careful planning. But as these examples demonstrate, the result can be pure magic.  Me and “Shadowfax”

Me and “Shadowfax”