By James Tricker

The repeat photography undertaken at the Mountain Legacy Project (MLP) requires thorough preparation before the season starts, and long days in the field hiking to remote peaks and promontories, as Claire and Daniel recount in their climb up Mt Alderson (“A Day in the Field: Going up Mt Alderson”). Although every outing presents its own challenges, each ascent brings the same reward: locating the precise position of the original camera stations and carefully recapturing the images. Standing in the correct spot decades (or even more than a century) since the original photographs were taken is an extremely satisfying accomplishment. It also generates a sense of kinship with all of those who have done this before.

James Tricker negotiating a bloated summit cairn on Mount Tekarra in Jasper National Park Photo credit: Shima Tajarlou

James Tricker negotiating a bloated summit cairn on Mount Tekarra in Jasper National Park Photo credit: Shima Tajarlou

The process for figuring out camera locations begins months in advance of heading into the field. After obtaining historical photographs from Libraries and Archives Canada, MLP researchers use Google Earth to estimate station locations. There is an art to this task and longtime MLP collaborator, Rob Watt, is the undisputed master due to his keen eye and vast knowledge of the Canadian cordillera. Next, the images for each station are gridded, printed and organised into binders to carry into the field.

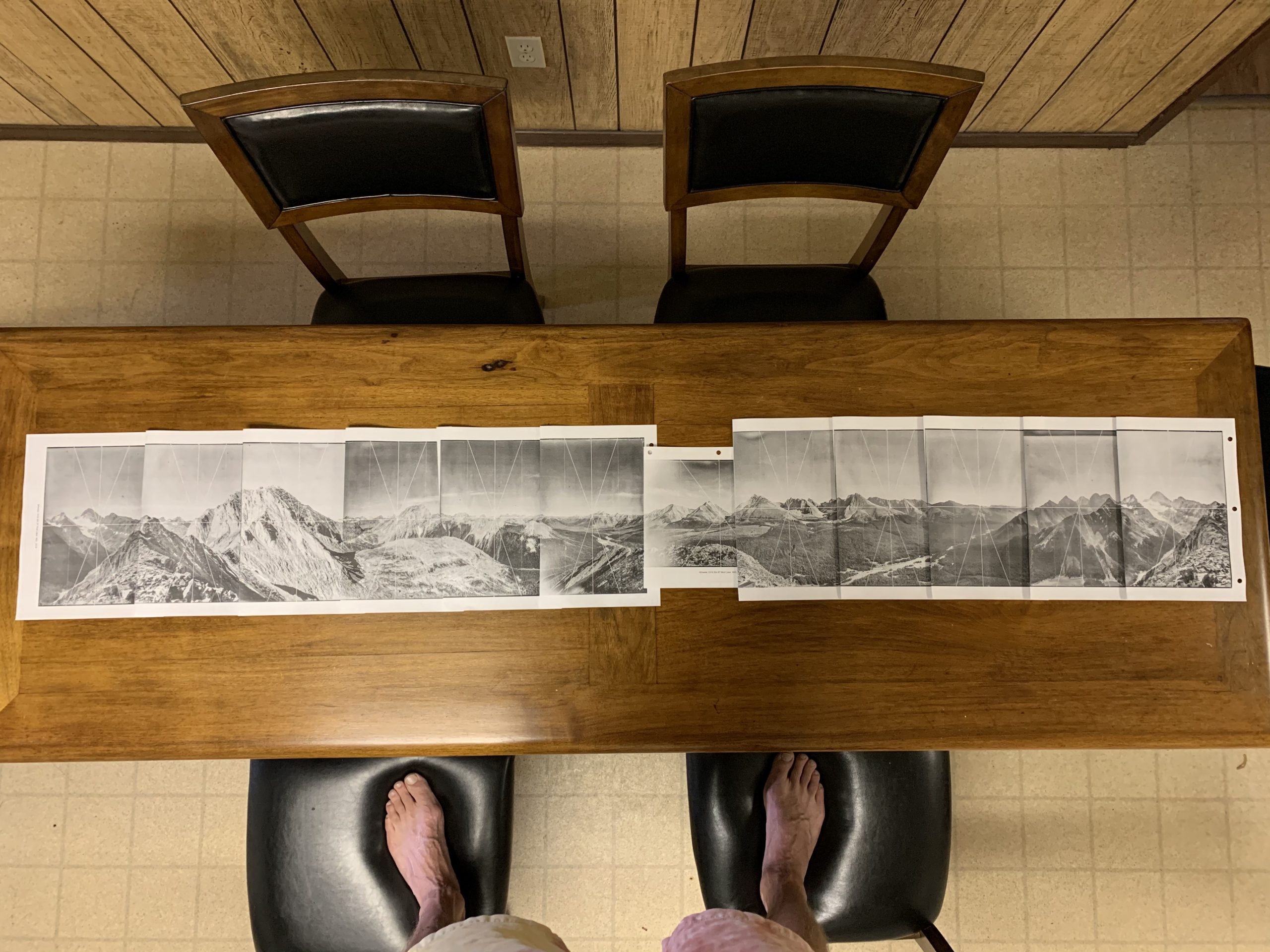

A beautiful panorama of historical photographs captured by A.O. Wheeler from Station 67 Mud Lake in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park for the 1916 Interprovincial Boundary Survey

A beautiful panorama of historical photographs captured by A.O. Wheeler from Station 67 Mud Lake in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park for the 1916 Interprovincial Boundary Survey

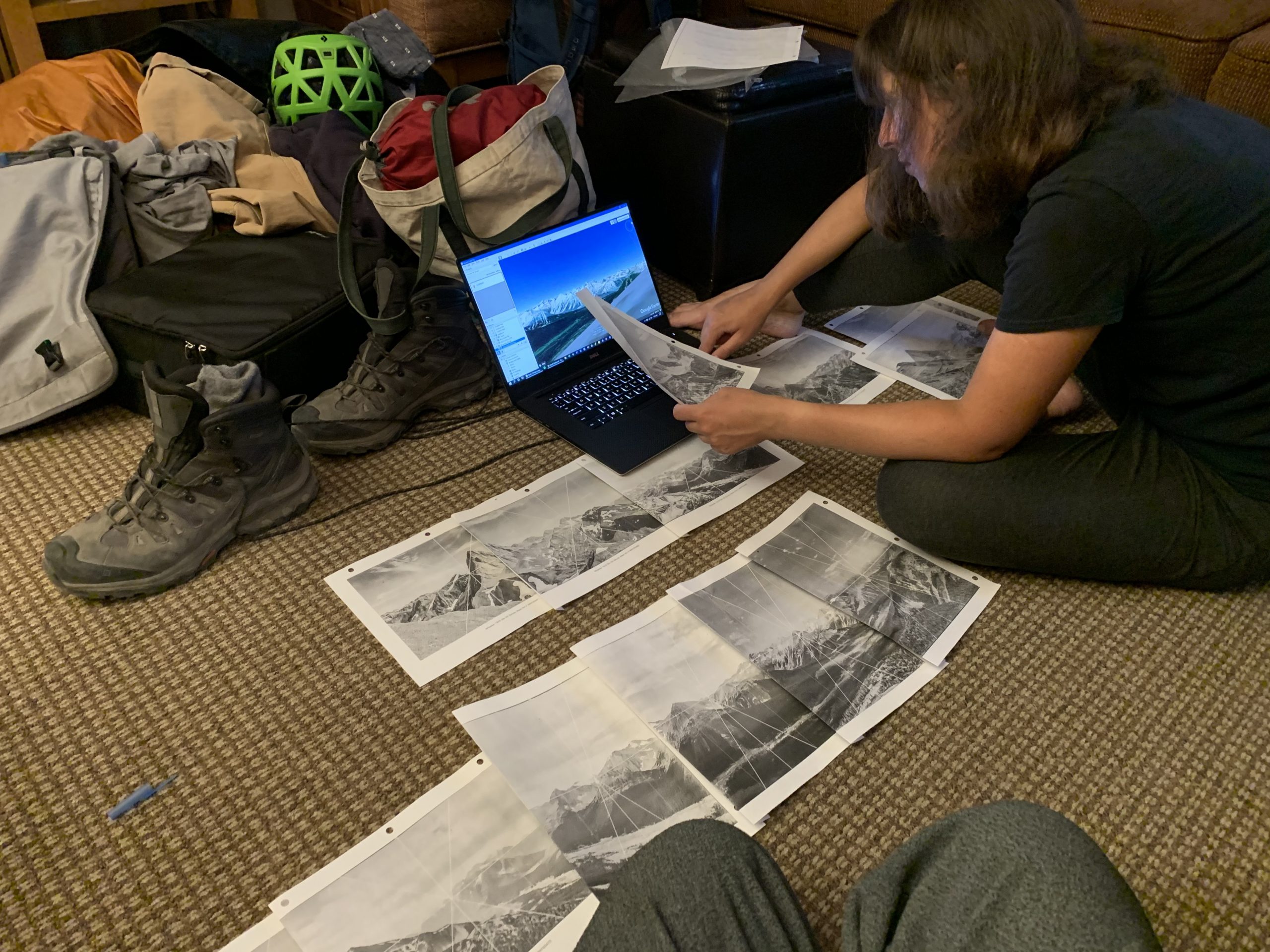

The evening before an ascent, the field crew will go over station logistics (i.e., what type of access, distance/elevation gain, on or off trail, etc.), double check the station location in Google Earth and get refamiliarized with the historical images. This involves laying all the images out and matching them together to see if they create a panorama (i.e., to make sure they were all taken from the same spot). This is also the time to identify distinctive foreground features and other clues such as specific aspects of adjacent mountains that will help fine-tune the camera location. The images are then labeled in the order they will be repeated. Heading to bed, the crew will have a pretty good idea about the clues to look out for the next day.

Sonia Voicescu checking locations and prepping images the night before a day in the field

Sonia Voicescu checking locations and prepping images the night before a day in the field

Moving up the trail, crew members will begin to see familiar scenery that was rendered on Google Earth the previous evening. Getting closer to the station, the specific angles and proportions of nearby terrain features visible in the historical photographs become apparent. Closer still, the precise location of the camera station is often dictated by the immediate topography. Peaks with small summits are typically easy to figure out – there simply aren’t many places to put a tripod. Broader peaks may have multiple camera locations to enable unimpeded views in all directions; likewise, more subtle promontories or rounded ridges can be challenging to figure out. Areas of flattish ground with panoramic views typically hold promise. Other clues are provided by the immediate foreground in the historical photographs – distinctive rocks or specific landscape features that help home in the location. However, it’s important to be open-minded when considering these clues as it’s often hard to gauge their actual size. Sometimes a feature can look bigger in the photograph than it is in real life, and at different times of day, shadows will be cast that further complicate interpretation.

Caitlin Mader and James Tricker fine-tuning a camera location from McArthur’s 1900 survey in Kluane National Park Photo credit: Ellen Whitman

Caitlin Mader and James Tricker fine-tuning a camera location from McArthur’s 1900 survey in Kluane National Park Photo credit: Ellen Whitman

There is one clue that usually trumps all others – the unmistakable cairn. Surveyors frequently built cairns after taking their photographs and sighting these usually means much of the detective work is over. However, all of the photographs may not have been taken from the cairn – a second (and third) location may have been used to provide better views in certain directions. Another very real problem is the original cairns on popular summits have grown significantly larger due to hiking parties stacking on additional rocks (sometimes gathered from the foreground of the photographs). I can think of numerous summit cairns so bloated it is impossible to get the camera in the correct location. That issue aside, the cairns provide tangible evidence that the surveyors once stood in the exact same spot all those years ago.

Kristyn Lang next to a 100-year-old cairn built by A.E. Wheeler in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park

Kristyn Lang next to a 100-year-old cairn built by A.E. Wheeler in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park

In Jasper National Park, I’ve been fortunate that the stations in my study area were previously repeated 25 years ago by Drs. Jeanine Rhemtulla and Eric Higgs. Over the course of three intense summers between 1996-98, they located all 92 stations from M.P. Bridgland’s original 1915 survey, capturing a total of 735 images. They also recorded detailed station notes and, in most cases, captured station location photographs. This has made the process of returning to the stations and capturing the threepeat images much easier! Yet repeat photography remains a significant undertaking. Contributing to this ongoing legacy demands extensive preparation and planning, deep reserves of mental fortitude, physical endurance, a bit of detective work, and the occasional slice of good fortune. When it all comes together, it is truly one of the best jobs in the world!

All images are credited to James Tricker unless otherwise stated.