Jill Delaney, Lead Archivist, Photography, Private Archives, Library and Archives Canada

May18, 2021

I write this blog from the unceded traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg (Algonquin) peoples in Ottawa, Ontario. The historical photographs discussed in this post cover broad areas of Alberta, British Columbia, and Yukon Territory on Treaty 6, 7, 8 and 11 lands, including many unceded territories with no treaties. This acknowledgement is made both to acknowledge the long inhabitation of these lands by Indigenous, Métis and Inuit peoples, but also with the hope of building a better understanding of the archival photographs that form the foundation of MLP’s work.

At its core, rephotography is an archival project. It relies on historical photographs to build a narrative about change over time, and to help us to understand what is present today. The 28 million photographs at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), including the 60,000+ which form the foundation of the Mountain Legacy Project, are used by researchers to try to better understand Canada’s environmental and cultural histories. However, we can miss the deeper reading of their meanings without an understanding the photographs’ own past. In this post, I want to briefly touch on the history of phototopography, the history of the archival collection, and how LAC contributes to the Mountain Legacy Project.

Historical photography has an uncanny facility to convince us that we have unfettered access to the past, and perhaps none more so than scientific photography, of which survey photography is a part.Today, those photographs offer an incredible gift to help us understand landscape change in the region over a period of more than a century. But that analysis needs to be grounded in a deep knowledge of the diverse histories of the landscape itself, and in the history of the images. Both MLP and Library and Archives Canada are now looking to Indigenous, Métis and Inuit Peoples to help us understand more about the colonial origin of these photographs and what that might mean for their continued use by both settler institutions and the First Nations whose territories are depicted.

It is important to recognize that map-making is a key tool of colonization and control. If we dig into the history of photography we find that from its earliest days in the 1840s, photography was experimented with as a tool in creating borders and therefore cementing the geography of nations in both Europe and their colonies.

One of the earliest proponents of photography, François Arago (1786-1853), Minister of Defence of the French Republic, was also one of the first scientists to recognize the potential of photography to aid cartographic mapping. Experiments in the methodology continued to take place from the 1850s throughout Europe.

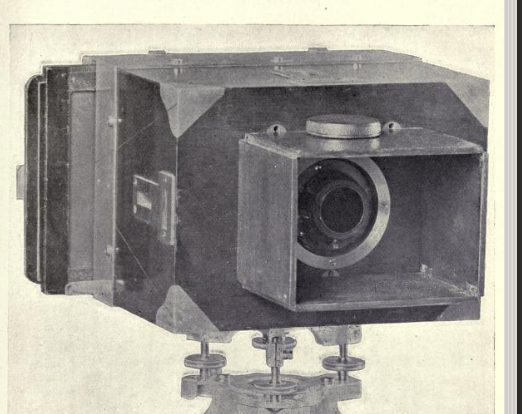

Here in Canada, we can draw a direct line between the French engineer and cartographer Colonel Aimé Laussedat, considered by some to be the inventor of photogrammetry, and Canada’s Surveyor General of the Dominion of Canada (1885-1924), Edouard Gaston Deville (b.1849-d.1924). It was Deville who implemented the comprehensive phototopographic survey in the Canadian mountains, conducted between 1887 and 1958.

The photographic surveys led to both the demarcation of provincial (for the Interprovincial Boundary Commission) borders, as well as borders between Canada and the US (for the International Boundary Commission). This also allowed federal and provincial governments to control and assign land and even water usage to various interests, including National Parks, mining and timber companies, ranchers, and more. All of these actions had broad social, cultural and economic ramifications for the Indigenous Peoples who continued to live within these newly occupied and demarcated regions.

Until 2002 the photographs from the Dominion Land Survey were under the custody of what is today Natural Resources Canada. Surveyors there recognized the value of the photographs not just for topographic mapmaking, but for the key colonial project of the identification of resources vital to Canada’s settler economy. Many of these photographs have turned up as prints in other departmental collections, such as the old Mines and Technical Surveys.

Fortunately for us, the vast majority of the plates were safeguarded by these surveyors until their transfer to LAC in 2002. It was Ian McLaren, Eric Higgs and their students Gabrielle Zezulka-Mailloux and Jeanine Rheumtulla who brought them to LAC’s attention and proved their archival importance in initial rephotography projects. We now also recognize that these photographs can help tell important stories of Indigenous inhabitation, knowledge, use and stewardship of these lands under their care, and need to be re-examined under this broader lens.

When the more than 60,000 glass plate negatives arrived at LAC, they were in very acidic and brittle envelopes and loaded into large cardboard boxes which barely supported their weight. Thanks to the generosity of Mountain Legacy Project, LAC was able to rehouse and recontainerize the complete collection in 2003. These precious and fragile plates are now stored in environmentally controlled vaults in LAC’s Gatineau Preservation Centre.

I am the Lead Archivist for LAC on the Mountain Legacy Project, and have been working with the MLP since 2002. But I do not manage this project on my own – there is a team of dedicated and enthusiastic archival and technical staff to create and describe the high resolution scans for MLP (especially Kayley Kimball, Assistant Archivist). Research has also been conducted to find documents which would help locate the original camera stations. Maps, photo indices, field notes, diaries, correspondence and reports have been unearthed to provide important contextual information, and to help identify the plates that came without specific descriptions. A web of graduate students, Rob Watt, Rick Arthur, myself and many others have contributed to this research, done at both LAC and in other archives and government departments.

Collaboration is also at the heart of the technical work to develop the best protocols for scanning the plates to the high resolution and precision required by MLP. We estimate we have now scanned, described and shared over 4000 images from the original historical negatives. In 2002 I would have never imagined that I would still be working on this fascinating archival project, but it continues to grow and evolve in ways that enrich our understandings of the historical photographs every day.

More Info:

Mountain Legacy Project’s Indigenous Territory Acknowledgement: Following Their Footsteps

Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada LAC/BAC: Website

An Inconvenient Truth? Scientific Photography and Archival Ambivalence. J. Delaney, 2008: Article