by Kristyn Lang, January 21st, 2021

Following our days spent exploring coal mining history in the Crowsnest Pass, our field crew headed North to Kananaskis Country. We spent three days working in lower elevation foothills before moving further west to spend our remaining days attempting higher elevation stations in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park and the border of Banff National Park. This area is this the focus of Maya Frederickson’s graduate research. With advice from Bill Snow of the Stoney-Nakoda First Nation, Maya is attempting to understand the legacies of Indigenous patterns of fire as a traditional land management practice in the Canadian Rockies. Due to a last-minute family emergency, Maya was unable to join us in the field. Fortunately, Sonia and James took me under their wing and showed me the ropes of MLP fieldwork so I could fill in as an undergraduate volunteer. After a summer of cancelled plans due to Covid-19, I was so grateful for the opportunity to get out into the field!

The initial lower elevation stations brought their share of challenges with tree regrowth. Despite not being able to get all of the photographs from Mount McNab, it made for an educational day where James and Sonia shared route finding tools and tips and I gained confidence taking photographs from alternate locations, adjusting to tree regrowth obscuring our views.

Our next station invited me down memory lane as it followed a horse packing trail that I remembered from childhood. Along the way, there was a large swath of logged forest that left behind a sobering tangle of deadfall. This made for a ghostly but more accessible hike to the top of the hill and the photographic station. In the distance, we heard the songs of cows in the foothills.

We were gifted with some superb weather conditions during the first leg of Kananaskis, but the threat of rain is always important to keep in mind while in the field. We decided to hike one of the higher elevation stations in Spray Valley while the weather held up. The drive to the trailhead filled the whole team with excitement as we were greeted by two grizzly bears on the highway. We gazed upon the most dramatic peaks we had seen thus far. The hike to Station 67 from the Wheeler 1914 survey on Commonwealth Ridge posed some challenges as it is not a highly trafficked route. Following a steep bushwhack to the summit, we arrived on the Ridge with clear views of Mt. Chester and Smutwood Peak, both prominent and providing promise for our days ahead.

Left: James and Sonia enjoying the ridge walk along Commonwealth Ridge. Image: K.Lang, 2020.

Right: Sonia and I navigating dead fall on our way down from Station 67. Image: J.Tricker, 2020.

The second portion of Kananaskis Country consisted of two helicopter days and a lasting-memory hike up Smutwood Peak. Mount Smuts, which is located on the same ridge, is named after South African statesman, military leader, and lawyer Jan Smuts who was recognized for his love of the mountains (Brush, 1984). He was celebrated for his accomplishments such as his role in establishing the United Nations, becoming the President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and publication Holism and evolution in which he coined the term “holism” (Shelley, 2005). However, Smuts’ legacy is clouded by South African policies of Apartheid.

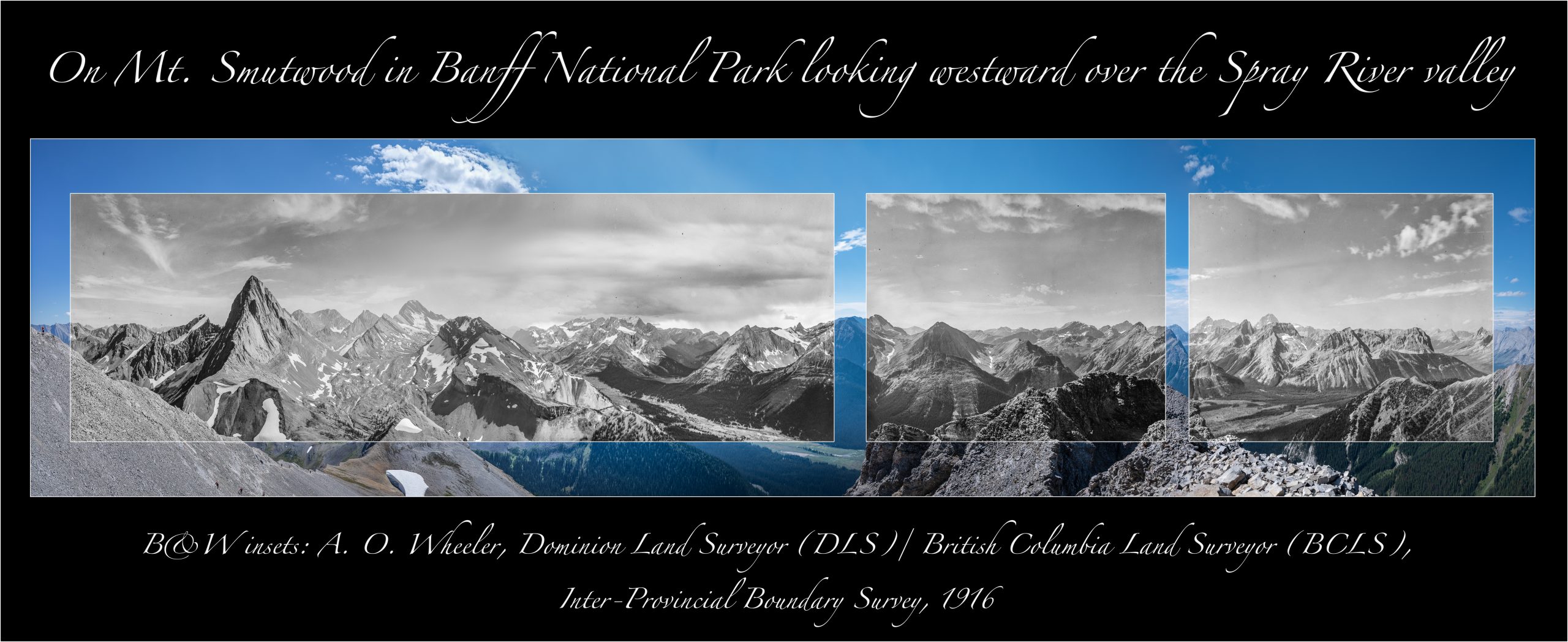

The 20 kilometer trail led us through the landscape in its elevational stages, into a beautiful open alpine meadow, and up the scree slopes with views of two alpine lakes. Smutwood Peak consisted of two stations surveyed by Arthur Wheeler in 1916, neither of which sat on the true summit. This was one of many challenges we faced as we were met by 50 km/hr gusts, a daunting scree slope, and classic Rocky Mountain exposure. I found the first station on the opposite side of the ridge from the true summit, which marked a memorable moment as the first station I photographed independently (Station 50 pictured below). Sonia held down the fort on the main summit as 15 hikers approached, buzzing with questions about what we were up to. The second station was trickier to locate but James was able to successfully find a safe route, which made for a long but rewarding day. We hiked down with a sense of accomplishment as we watched the sun fall behind the mountain; we parted with pink skies.

The following days were spent wearing masks in helicopters, thanks to in kind support we received from Alberta Agriculture and Forestry organized by Rick Arthur. Our first day of helicopter support was spent shooting the two stations from a hover as they were obscured by trees, and an attempt was made to land on the sharp peak of Mt. Chester. Due to strong winds and the high volume of hiker traffic on the summit, we were unable to land. After a long day spent in the air, we were able to enjoy some socially distanced homemade woodfired pizza with Rick and his wife, Naithene. On the last day, Rick managed to organize a final bump to Mt. Chester where James and I successfully completed the last station for Maya’s research work. This marked the completion of 8 stations and with some high elevation stations under our belt, we were ready to head North to the Athabasca River Valley in Jasper National Park.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of our Fieldwork series to hear more about James Tricker’s research in Jasper.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Rick Arthur and the Alberta Agriculture and Forestry Elbow River base for their efforts that were essential to our success in Kananaskis. On behalf of Maya Frederickson, I thank Bill Snow for making Maya’s research and our work in Kananaskis possible.

Additional Information

About Me

I am an undergraduate student at the University of Victoria pursuing a double major in Earth Science and Environmental Studies. I have been involved with the MLP since January of 2020 after a guest lecture from Eric Higgs. This past summer, I had the opportunity to assist Mary Sanseverino with building vegetation land cover masks, virtual photos, and georeferenced viewsheds using MLP software for a research project in collaboration with Landscapes in Motion.

Sources

Brush, F. W. (1984). Jan Christian Smuts and His Doctrine of Holism. Ultimate Reality and Meaning, 7(4), 288-297. doi:10.3138/uram.7.4.288

Shelley, C. (2008). Jan Smuts and Personality Theory: The Problem of Holism in Psychology. In 1157613288 869616121 J. Carlson (Author) & 1157613289 869616121 K. Pringle (Ed.), Striving for the Whole: Creating Theoretical Synthesis (pp. 89-109). Somerset, NJ: Transaction. http://centroadleriano.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Shelley-Holism-Chpt..pdf

Further reading on Jan Smuts:

Dubow, S. (2019, May 18). South Africa’s Racist Founding Father Was Also a Human Rights Pioneer. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/18/opinion/jan-smuts-south-africa.html