By Kristen Walsh and Mary Sanseverino.

With Rick Arthur, Winston Delorme, Bill Snow, and Rob Watt.

May 12, 2020.

MOUNTAINS make up one quarter of the Canadian land mass. They have been home to a vibrant diversity of Indigenous Peoples for thousands of years. In this blog post, we wish to acknowledge the traditional, and in some cases unceded, territories of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit upon which we carry out our repeat photography fieldwork. In an era where efforts at meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous peoples are being made, it is important to the Mountain Legacy Project that we wholeheartedly acknowledge the peoples whose land we move through, making our work possible and meaningful. Currently, our fieldwork stretches over Alberta, British Columbia, the Yukon and the Northwest Territories on Treaty 6, 7, 8 and 11 lands, including much unceded territory where treaties were not signed.

This map is a work in progress. For corrections and feedback, visit Native-Land.ca

The Mountain Legacy Project (MLP) bases much of its work on historic black and white photographs borrowed from archives (notably Library and Archives Canada) to conduct repeat photography in the mountains. As part of the overarching and problematic colonial apparatus in the late 1800s and first half of the twentieth century, Dominion Land Surveyors were tasked with surveying mostly western mountains using a complex and comprehensive technique that combined photography and trigonometry.

From these photo-topographic surveys, intricate maps were drawn up by surveyors. The maps, along with the recently constructed Canadian Pacific Railway, fueled the country’s westward settlement expansion. Subsequent surveys conducted with the same techniques by various other Federal and Provincial agencies mapped out potential mineral resources. And, while the mappers of these mountains were not involved with development and settlement per se, it’s important to highlight that this westward expansion forced the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories, saw the creation of reserves and residential schools, and the abolition of significant sociocultural and spiritual practices under the Crown’s devastating assimilation and injunction policies.

Albeit initially grounded in a colonial endeavour of the 19th century, we feel the images can be reclaimed — or examined through a different lens — to tell new stories that highlight Indigenous voices and raise social awareness about the cultural and environmental history of these precious places.

Stories through another lens

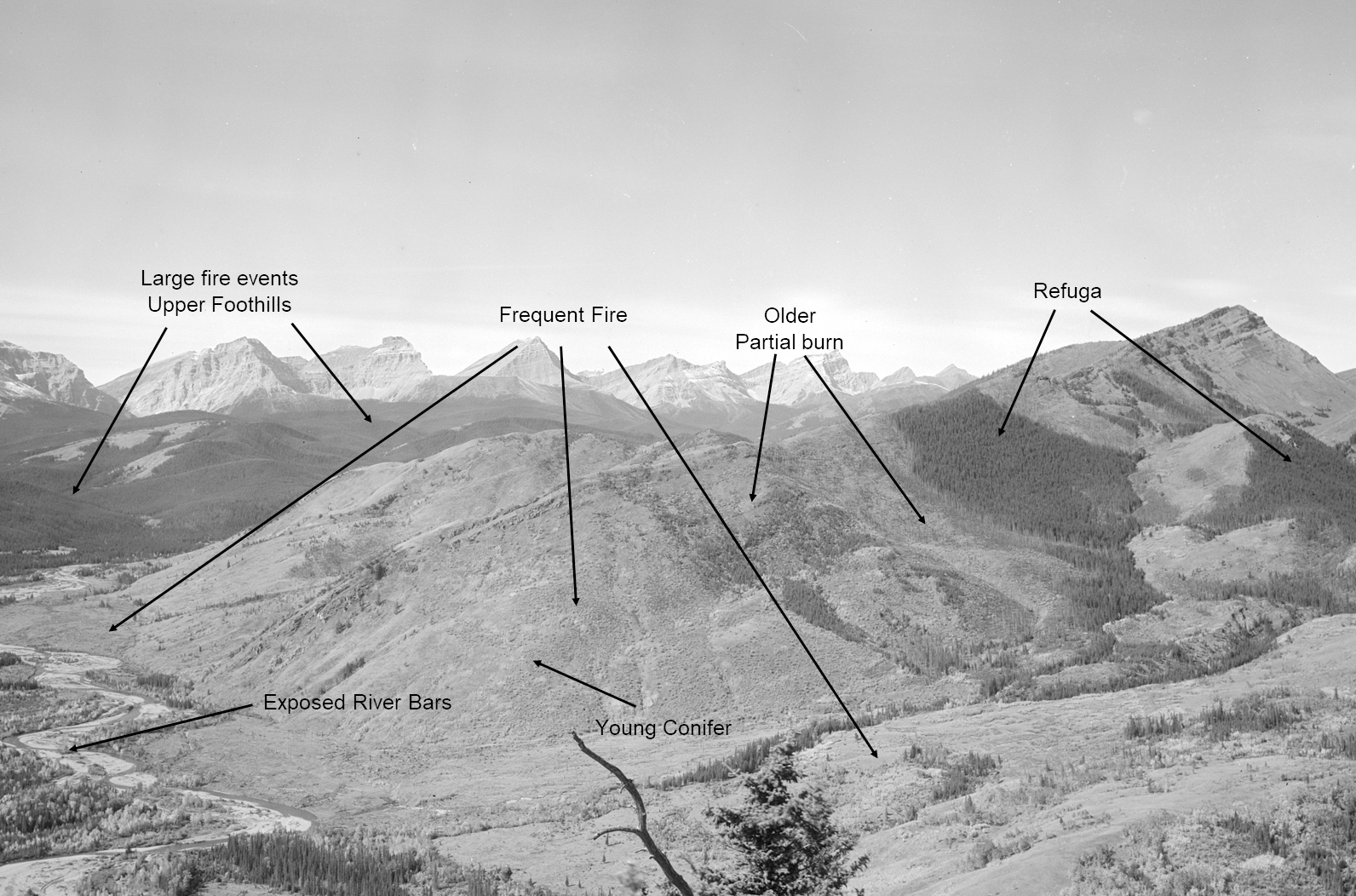

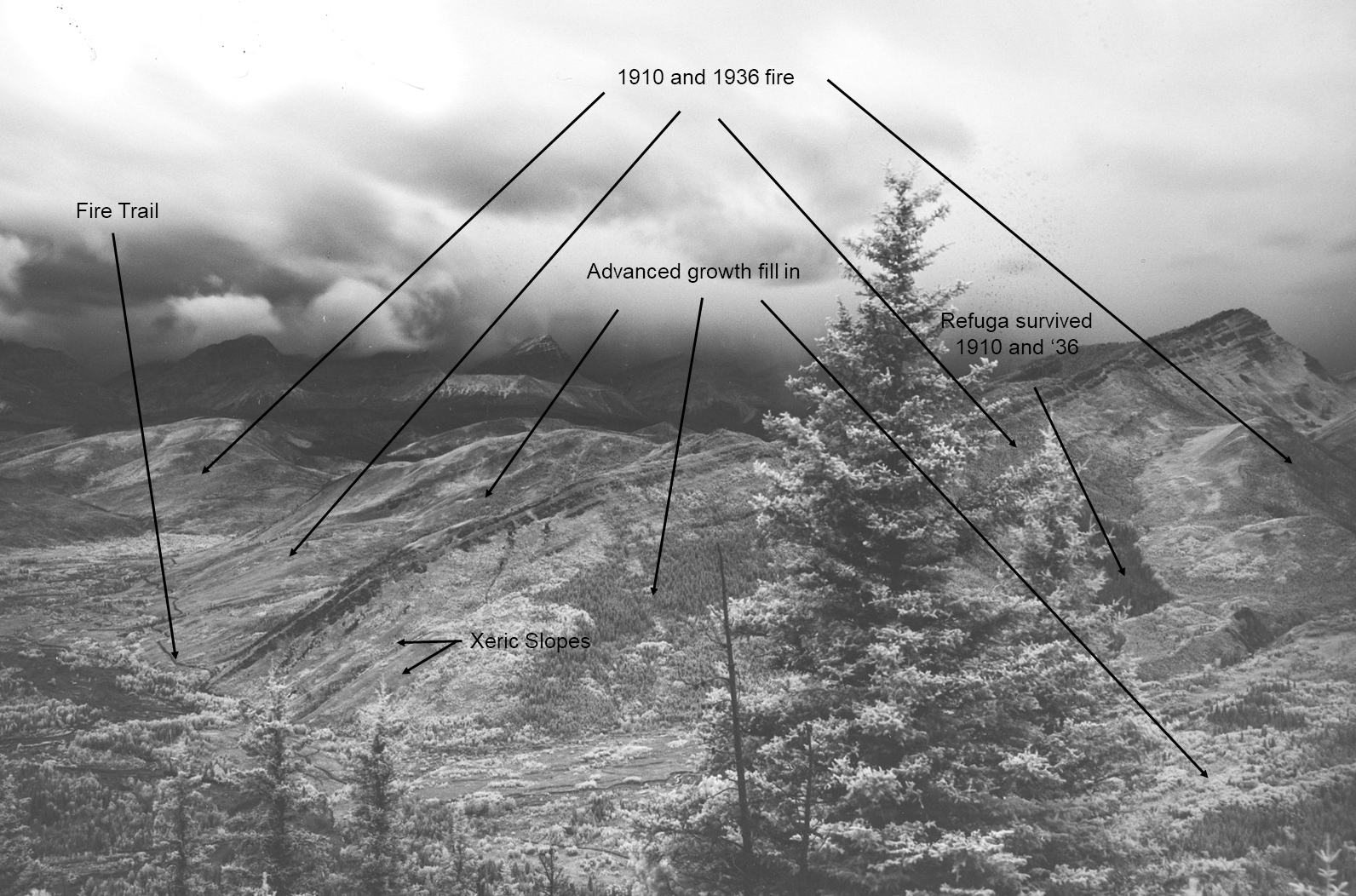

One of the prohibited sociocultural practices that is perhaps most apparent in the Mountain Legacy collection is the skillful use of fire by many different Indigenous groups as a means to manage the landscape.

Indigenous Burning Practices

In early spring and late fall frequent low severity burning was used by Indigenous peoples to keep invasive vegetation and species (such as ticks) in check. It also renewed wildlife habitat and protected medicinal and edible plants. Indigenous burning practices were disallowed following the signing of Treaty 7 in 1877. As well, the Pass and Permit System instituted by the Canadian government in 1885 prevented First Nations from leaving their reserves without permission. This further limited their access to traditional territories, thus impacting burning practices. These actions contributed to the exclusion of fire on the landscape and have encouraged the development of homogeneous, mature coniferous forest stands in fire prone ecosystems. This poses a significant fire risk today.

Info courtesy: Rick Arthur, Research Associate with the Mountain Legacy Project.

Examine more historic and modern images from this location at explore.mountainlegacy.ca.

Trade and Travel Routes

Historically, this valley and the pass at its head, along with its associated trails, such as the Buffalo Cow Trail, had been used for centuries by the Ktunaxa people of the Tobacco Plains. The foothills and grasslands were home to both the Piikáni and Kainai. The wealth of archaeological sites here in the Blakiston Valley and adjacent plains attests to long standing and frequent occupation of the area.

Info courtesy: Rob Watt, Research Associate with the Mountain Legacy Project.

Examine more historic and modern images from this location at explore.mountainlegacy.ca.

Outfitting and Hunting

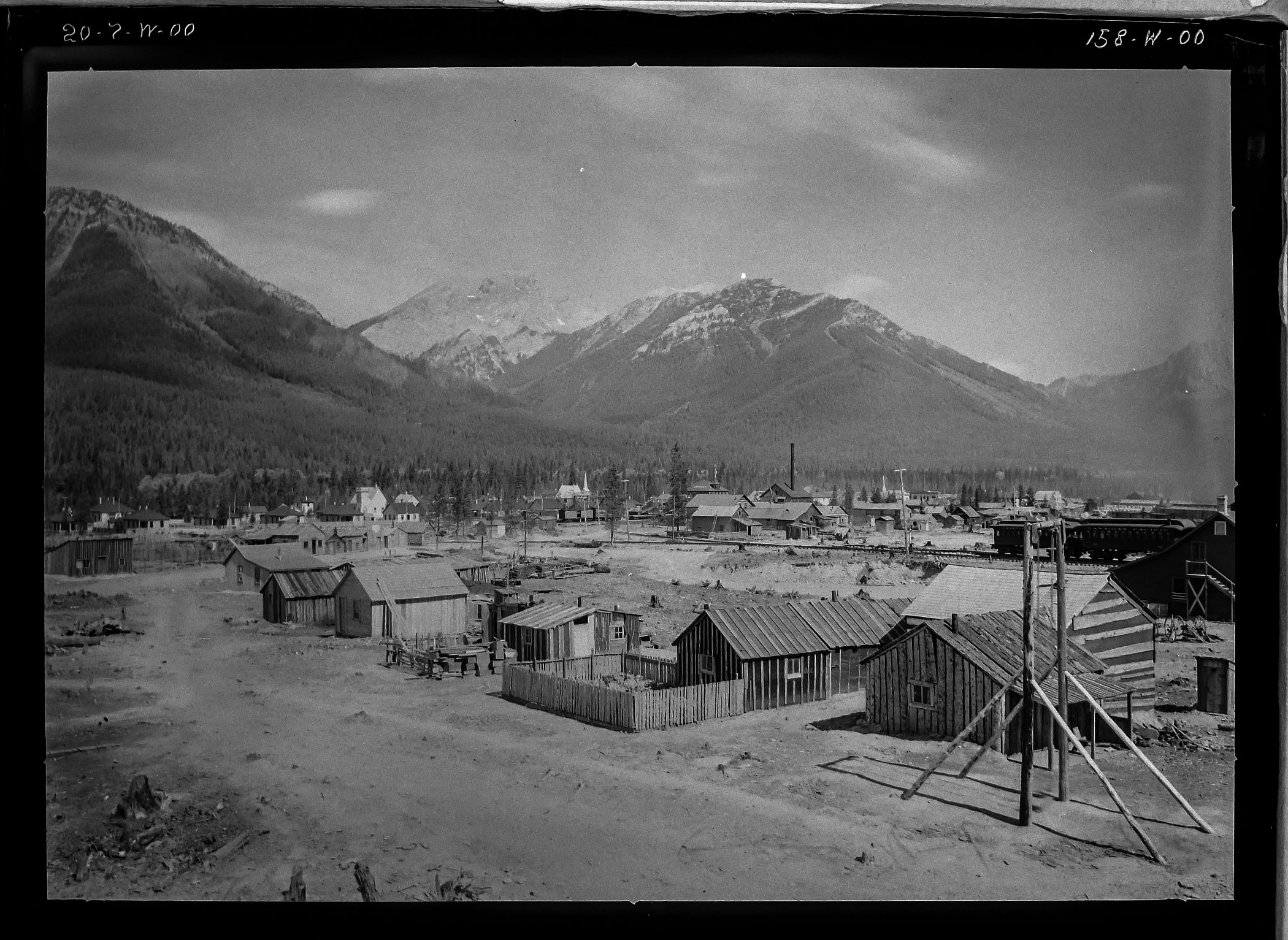

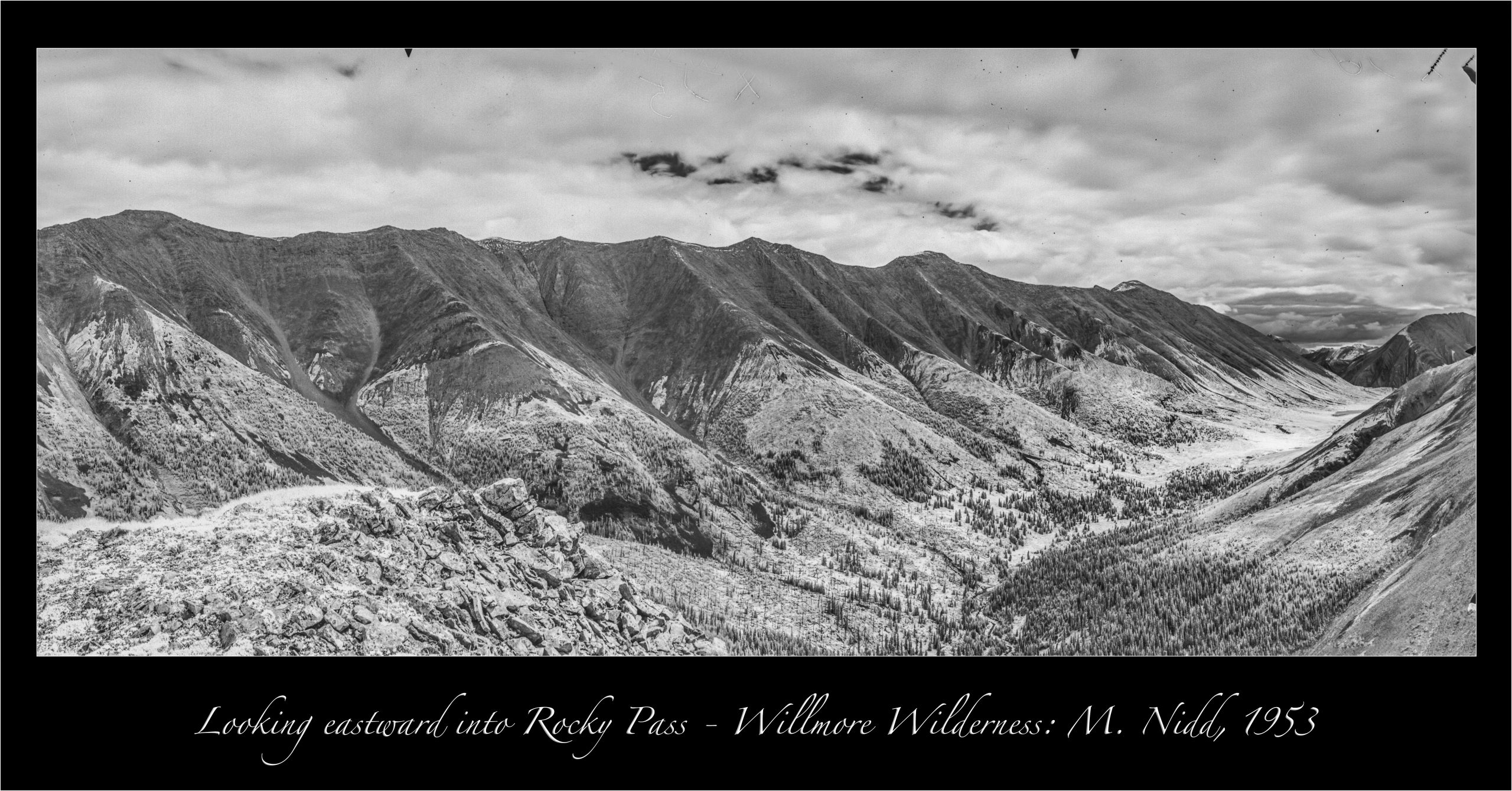

Indigenous and Métis outfitters and hunters adeptly moved through the mountains surrounding Grande Cache, Alberta, and throughout what is now known as the Willmore Wilderness Area, particularly the areas of Rocky Pass and Big Graves.

Info courtesy: Winston Delorme, Métis, Grande Cache, Alberta

Examine more historic images from this location at explore.mountainlegacy.ca.

Sacred Places

We recognize that some of the places where surveyors took photographs are areas of sacred significance, like Moose Mountain in Kananaskis Country, or vision quest sites, particularly in the Kootenay Plains area.

Indigenous Place Names

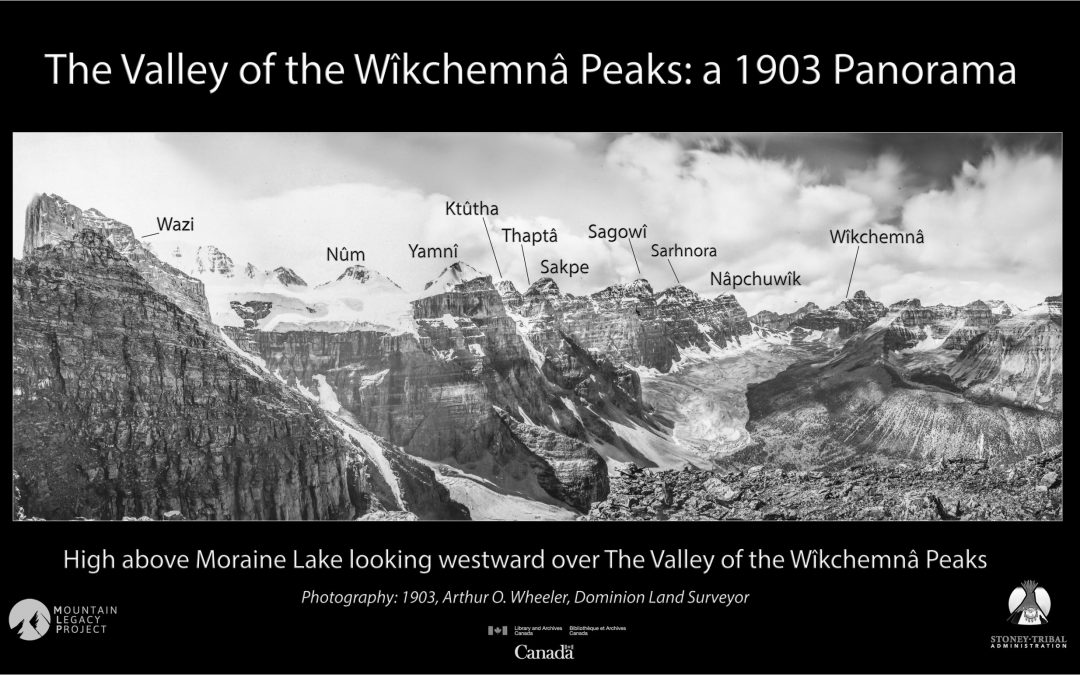

In day-to-day practices and in our research, we acknowledge, use, and encourage others to use Indigenous place names, such as the Stoney Nakoda names for mountains in the Ten Peaks area of today’s Banff National Park – for example, Ktûtha [4], Nâpchuwîk [9], and Wîkchemnâ [10].

Tonsa, Neptuak, and Wenkchemna were the place names given in 1894 by explorers Samuel Allen and Walter Wilcox, and Nakoda guide Enoch Wildman. They are the names that exist on today’s maps. The change to Ktûtha, Nâpchuwîk, and Wîkchemnâ better reflects the Stoney Nakoda language.

Info courtesy: William (Bill) Snow, Stoney Nakoda Nation.

Examine more historic images from this location at explore.mountainlegacy.ca.

We only scratch the surface in this post, but hope the MLP’s collection of imagery may be a source of future collaboration to help meaningfully unpack the depth of stories about these special, long-inhabited mountainous places.

More information

Fires of Spring: Hank Lewis, 1980. Fires of Spring is a 16mm film made by Dr. Henry T. Lewis, Professor of Anthropology, University of Alberta. It captures some of his life’s work and research related to the historic use of fire by Indigenous peoples.

These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places: the Story of the Stoney People by Stoney Elder Chief John Snow (1933 – 2006).

Bison Reintroduction Project – EPISODE 3: Burning for Bison.

The Bison Reintroduction Project in Banff National Park. A burn of the Panther Dormer area in the park is helping to revitalize the food supply in the Bison Reintroduction area.

The Shining Mountains by Zac Robinson and Stephen Slemon. Alpinist Magazine, Dec, 2016. In Alpinist 50, Zac Robinson and Stephen Slemon depicted some of the ways in which the original mountain people of the Canadian Rockies made exploration in the region possible, and how their names for local mountains, such as “The Shining Mountains,” came to be written over.

Read the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future.

Canadian Mountain Network – new directions to support Indigenous research and research training in Canada 2019 – 2022.