By Jess Duncan, Sept 15 2020

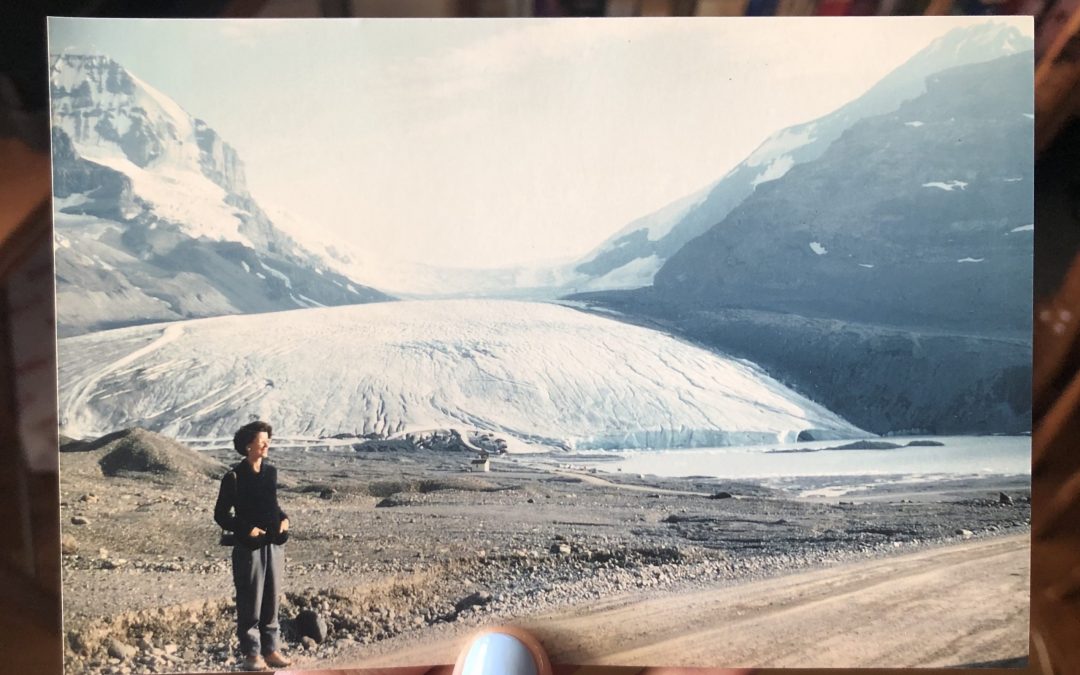

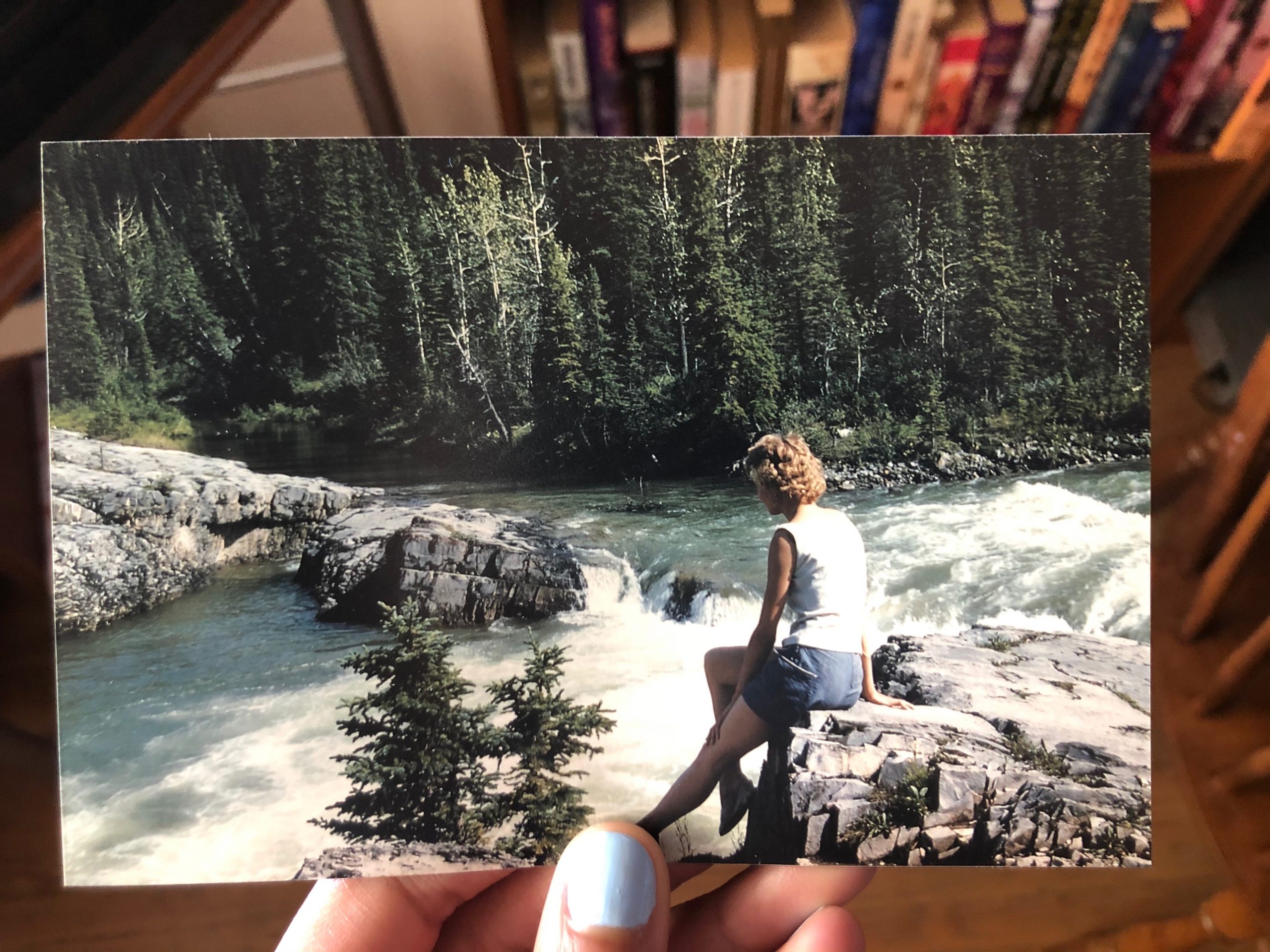

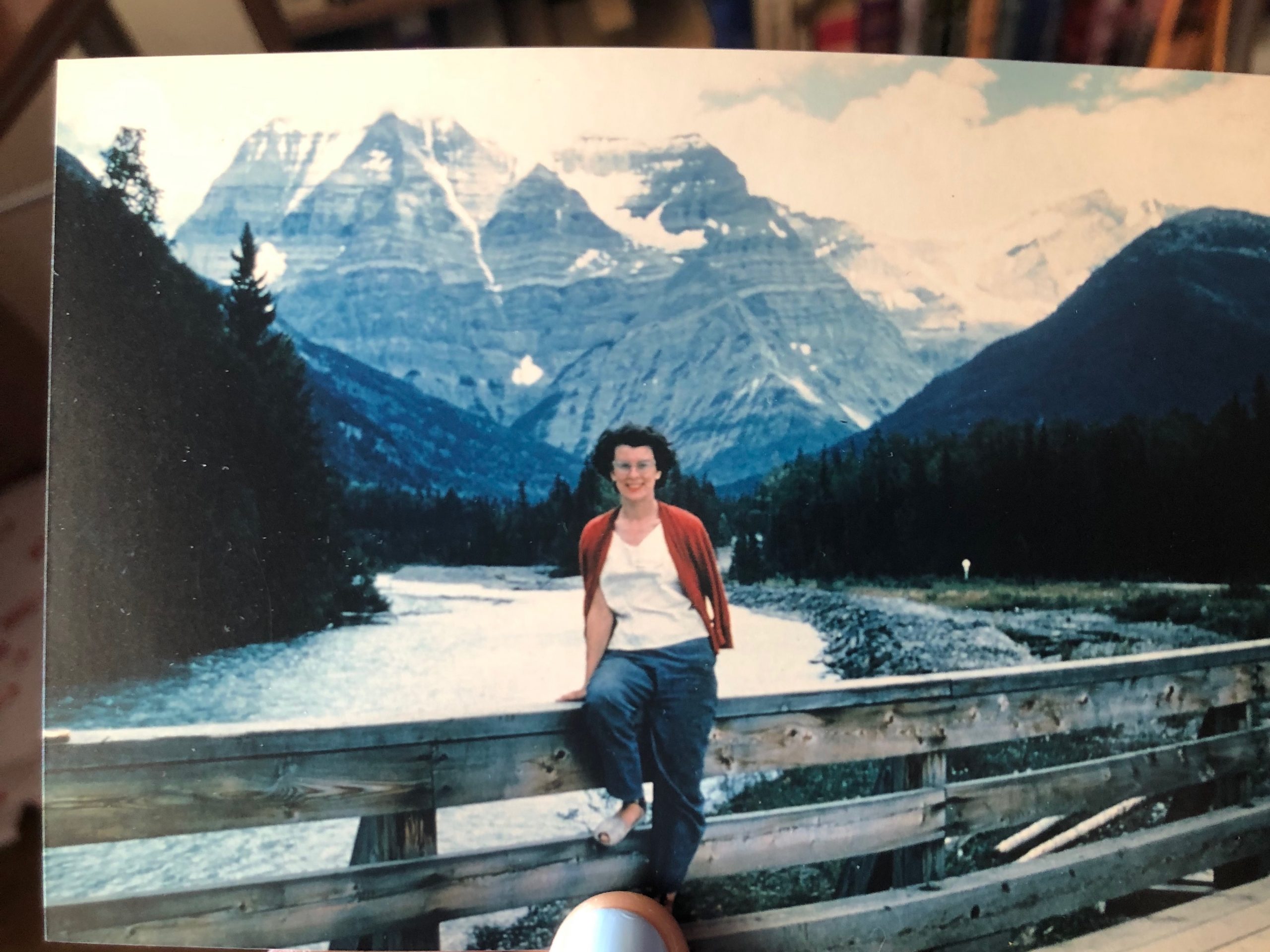

In the mid 1950s, two young women in their twenties from the UK came to Canada to embark on a cross country road trip. They travelled across Canada, down through the States and into Mexico. The pair encountered many characters on their ambitious trip, and took many photos of vistas that left them in awe. These women were my grandmother, Janet, and her best friend Carol.

I am grateful to see their pictures and imagine what that same trip would be like now. How have these landscapes changed? This August I was able to see for myself as I partially retraced their steps on a camping trip from Jasper National Park down the Icefields Parkway into Banff National Park.

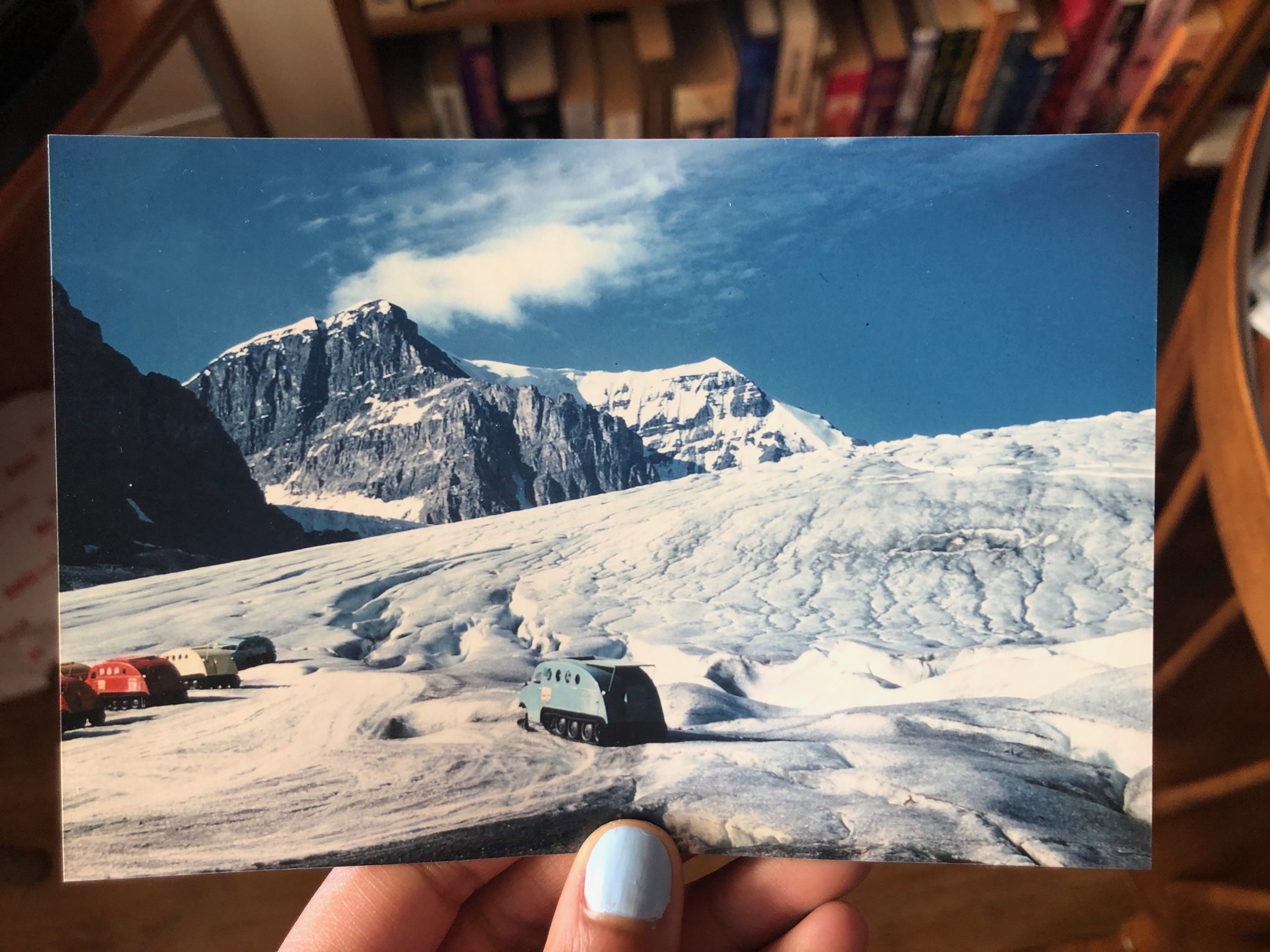

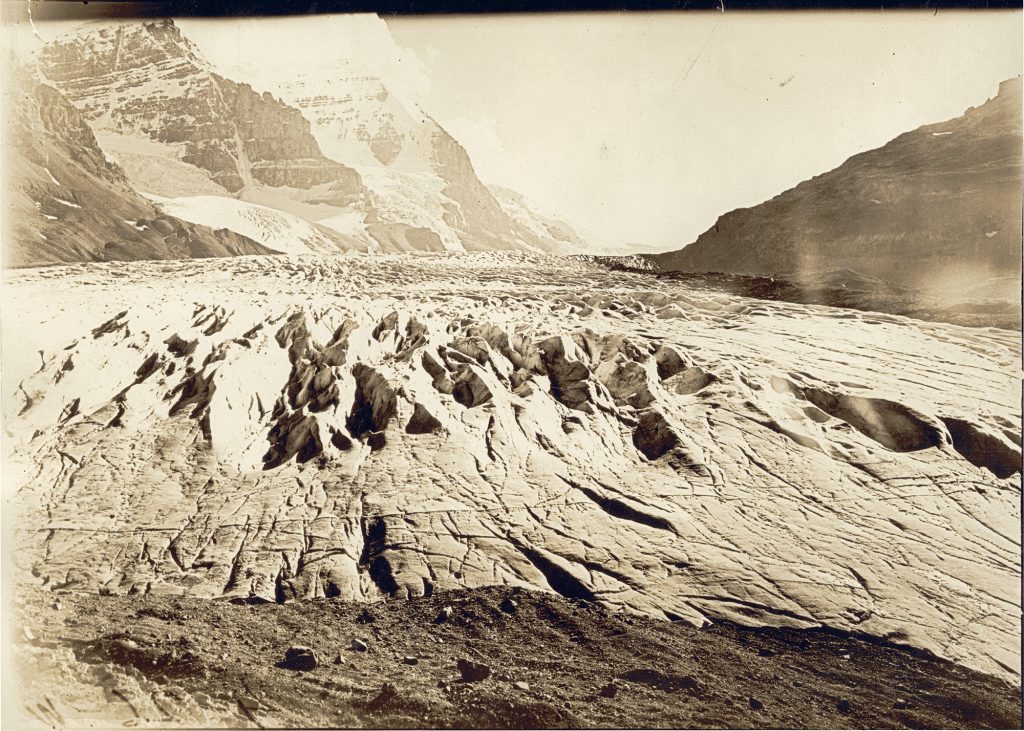

Within the Columbia Icefield lies the Athabasca Glacier, the most visited glacier in North America. Along the pathway from the parking lot to the toe of the glacier stone markers indicate the glacier has receded about 2 km since 1750 (Bailey and Van Tighem, 1987). On average, the glacier retreats 5m every year (Graveland, 2014; Weeks, 2018). It is enough to make an environmental studies major like myself feel nostalgic, scared, impressed, mournful and intrigued all at the same time.

The Columbia Icefield is the hydrographic apex of Canada; meltwater from the six main glaciers in the Icefield (of which Athabasca is the largest) flow into the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic oceans. The disappearance of the Athabasca Glacier, which is expected within the current or next generation, has serious global implications for ocean circulation patterns, sea level rise, hydro-power production and fisheries (Graveland, 2014).

Visualization tools, like the markers, are key to understanding impacts of climate change. As humans we must have A personal connection to something in order to care about what happens to that thing in the future. Being able to see exactly how far the glacier has receded in the last hundred years is eye opening, but not everyone has the opportunity to travel to Canada’s national parks and experience the vastness of glacial retreat, the seeming impossibility of the mountain pine beetle, or any other environmental challenges plaguing the flora and fauna of the Canadian Rockies. Enter Mountain Legacy Project (MLP).

Right: Repeat photo of Athabasca glacier in 2011 taken by the MLP field team. Image courtesy of the Mountain Legacy Project.

One of the things I love most about MLP is its universal accessibility to the general public. Similar to the joy and wonder that come from rummaging through old family photos, anyone in the world can be transported into the Canadian rockies to see any changes between pictures taken by explorers from 1890-1950 and repeated by modern day researchers.

As a research assistant at MLP I have been trusted with the back-end task of making modern photos and notes from the MLP field team and historic photos from Library and Archives Canada available for the public to view. For my work I have sifted through thousands of photos, old and new, of places I have never visited. I have seen rivers rerouted, mines built and abandoned, towns and cities formed, glaciers retreat and the evolution of hiking attire. When I finally got to see so many of the peaks I have stared at on a screen in person this summer, I felt an incredible sense of familiarity. I invite you to grab a snack or a coffee and head to explore.mountainlegacy.ca, and be transported into the vast and ever-changing Western Canadian Mountains right from your computer.

REFERENCES

Bailey. E. and Van Tighem, K. 1987. Columbia Icefield: Ice apex of the Canadian Rockies. Ministry of the Environment, Calgary, AB.

Graveland, B. 2014. Athabasca glacier melting at ‘astonishing’ rate of more than five metres a year. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved on September 3 2020 from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/athabasca-glacier-melting-at-astonishing-rate-of-more-than-five-metres-a-year/article18835512/

Weeks, P. August 10 2018. The Incredible Shrinking Glacier. Universities Space Research Association. Retrieved on September 3 2020 from https://epod.usra.edu/blog/2018/08/the-incredible-shrinking-glacier.html

MORE INFORMATION

http://explore.mountainlegacy.ca/historic_captures/5571 This photo from Arthur Wheeler in 1897 shows Elbow Falls as part of the Canadian Irrigation Survey. Surveyors sit on the rock where Carol sits in one of the previous photos.

Columbia Icefield: A Solitude of Ice by Don Harmon & Bart Robinson contains beautiful photos of the entirety of the Columbia Icefields as well as useful information about the understanding glacial movement, geography and history.

Carol standing on the canoe docks at Moraine Lake, Valley of the Ten Peaks in Banff National Park, July, 1958.

Moraine Lake in August 2020, photo taken by me (Jessica Duncan)